A Town Like Alice

Surviving war in its wake

By William Wetherall

First posted 1 September 2006

Last updated 1 September 2006

Hardcover editionsNevil Shute The Legacy Paperback editionsA Town Like Alice The Legacy The Legacy The Legacy Japanese translationNeviru Shuuto Nevil ShuteNevil Shute (1899-1960), born and educated in England, served as a soldier in World War I then became an aeronautical engineer and a writer. A well-known novelist by World War II, he served the final months of the war as a correspondent in Burma. After the war, Shute moved from Britain to Australia but seems to have remained a British national -- though some Australians call him an Australian novelist. Some of Shute's most popular stories -- like A Town Like Alice (1950) -- are set in Australia and parts of Southeast Asia. Alice Springs"A town like Alice" alludes to the attempts of a woman, who had survived capture and detention by Japanese in Malaya, to turn a small town in Australia into a prosperous community like Alice Springs. Much of the story about her captivity is revealed through an impossibly long conversation she has with the man who presumably narrates the entire novel. The hero, Jean Paget, an English woman who has survived years of captivity in Malaya during World War II, inherits enough money to allow her to quit her job. Though she wants to forget the war, she also wants to go back to Malaya to dig a well for the villages who had helped her (page 33, Pan edition). The narrator is Mr Strachan, the solicitor who facilitates the inheritance. For dozens of pages at a time, the narrative baton is passed to an omniscient third-person voice as Strachan's "I" -- and with it any sense of the present -- vanishes from the story. A secret family languagePaget had lived in Malay when a girl and learned Malay from her amah. After bringing her and her brother Donald back to England, her mother had made the children speak Malay among themselves, "first as a joke and as a secret family language, but later for a very definite reason": her father, who had remained in Malay, was on company business when he drove his car into a tree, and the company held a job open for Donald when he turned nineteen (page 34). Paget had been eleven and Donald fourteen they left Malay. She was sixteen in 1937 when he returned to Malay to take the job. The next year left school to become a shorthand typist, and in 1939, after the war broke out in Europe, she took a job in Malay with a company that wanted a shorthand typist who could speak Malay. For about two years Paget led a happy life. Then came Pearl Harbor, and the advance of the Japanese Imperial Army through Southeast Asia. Paget soon found herself a captive at Kuala Penang. The men were marched off to a camp and the women and children kept separately. Captain YoniataThe officer in charge of the women and children is Captain Yoniata. A stern-faced woman protests the conditions and asks for beds and mosquito nets (page 46).

The women and children are walked all over the country to keep them occupied, as there is no camp for them. Weeks later they see two white men working on two trucks loaded with railway lines and sleepers, guarded by some Japanese. Aussie menThe party of women and children crowd around the trucks. Their guard begins talking in "staccato Japanese " with the truck guards (pages 73-74).

Mrs BoongThey continue to talk. Earlier in the story she had told another Japanese officer, Captain Nisui, "Seven of us have died upon the road already -- there were thirty-two when we were taken prisoner" (page 66). Now she tells the Aussie, "We haven't seen a doctor for the last three months and we've got practically no medicines left, so we mostly die. There were thirty-two of us when we were taken. Now we're seventeen" (page 75). He says to her, "If you're staying, Mrs Boong, we're staying too." He can fix the axle so it will never roll again. Does she need any medicine? She tells him what she needs. He disappears are returns with what she wanted and few other items. Alone, now, they continue to talk. She wonders here he's from and what he does. He's from Queensland but had been a ringer, a stockman, at a cattle station over a hundred miles southwest of "the Springs" -- Alice Springs, an oasis in the middle of Australia. She asks how many men takes to run the station (page 80).

He gets up from where he's been sitting, saying he has to get back to the truck (pages 82-83).

A tenuous bondJoe also gets the party some soap, and the other Aussie helps the Japanese get a pig, so the women and children get what the Japanese don't eat. When Joe promises a chicken, as well, Jean expresses her fear that he will get into trouble (page 90).

Joe is certain the war will be over in a couple of years and all they have to do is keep alive (pages 90-91).

The green sackFive black cockerels are delivered in a green sack by a Malay boy sent by a Chinaman Joe has done business with. They are still alive, and Jean gives the green sack with one chicken in it to their Japanese guard, a sergeant, saying "Gunso, good mishi tonight" (92). She tells him they have bought the fowls with money they were given by one of the Aussie prisoners. The sergeant wants a second but settles for just one. Everything seems to go well until Captain Sugamo, the local commanding officer, investigates the theft of twenty of his black leghorns with a green sack that had held grain for the fowls. The Aussies are hauled in because they had a reputation for petty larceny in the district. Sugamo's military police look everywhere but find nothing, until one day they spot the contingent of women and children, and walking with them, "a Japanese sergeant with his rifle slung over one shoulder and a green sack of the other" (page 94). Jean is slapped, kicked in her shins, stomped on with army boots, but she sticks to her story. The man she said gave her the money is brought before her at gunpoint. She sticks to her story (page 94).

Fates of Joe and SugamoAt this point in the story the narrative baton is briefly passed back to Mr Strachan (pages 94-95).

Awkward shifts in voiceThis reference to the fate of Captain Sugamo works because it is being told from a point in time looking back. However, the reader (and Mr Strachan) has already been told this and more about Sugamo, in an awkward aside two pages before this, at the beginning of the account of Sugamo's chickens. The aside comes right in the middle of a long stretch in which the narrative voice has remained in the past, to great affect. Then, when Sugamo is introduced as the commander in Kuantan, the voice suddenly breaks into the future to reveal what happened to him after the war -- before we have even read what he did in the novel (page 93).

Bushido stereotypesShute's execution of the novel has a number of flaws like this. Another involves a clumsy effort to explain Sugamo's behavior. Later in the narrative, in real time, we follow Paget to Malay, where she proceeds to dig a well in the village that had sheltered her the last years of the war. She asks them if they remember Sugamo. They recall that he was a bad man, that Captain Ichino, who came after him, was better. The villages did not know what had happened to Sugamo. Jean tells them -- and the reader is told for the third time -- that he had been hung as a war criminal. Here, though, it is revealed that "the Allies caught him when the war was over, and he was tried for murder, and executed in Penang" (page 123). The villagers are glad to hear this. She talks with them more Sugamo, and during the conversation she learns that the soldier who was beaten and crucified in the first year of the war survived. A villager tells her that Sugamo ordered the man taken down and the nails pulled out. This revelation, which is dramatized, is followed by an account of what Sugamo did to make sure Joe recovered. The account is only partly dramatized. Mostly it is an aside explaining why Sugamo did what he did -- beginning with the remark "It is doubtful if the West can every fully understand the working of a Japanese mind" (page 124). "Bushido" is twice mentioned in the speculation as to why Sugamo had Joe sent to a hospital. The whole aside is fresh out of a can of stereotypes, available at any East-West Mart. The reunionApart from such clunky interruptions in the narrative, Shute is a superb writer. He unfolds the temporal and spatial convolutions of his story both clearly and suspensefully. The tension builds slowly but surely, thanks as much to restraint and understatement than verbiage. Not until page 205 do Joe and Jean exchange a letter and telegram, having by then discovered what continent they are on. Then after just one more page, they finally meet again.

Sixteen pages later in the same scene, Joe asks Jean to marry him and she says yes (page 222). The last one-hundred pages of the story are, as they say, the future in Willstown, a small community in the Australian outback that, as they work hard, becomes like Alice Springs. The LegacyThe title in the United States was The Legacy, referring to what Jean went through in Malaya as much as to the inheritance that began her journey back to the future, as it were. The novel continued as The Legacy in the United States until the joint Australian-US production of "A Town Like Alice" in 1981 (see below). The tie-in edition of the novel bears the title A Town Like Alice, below which, in small print, are the words "Former title: The Legacy". How factual is Alice?Author's NoteImmediately after the story comes Nevil Shute's summary of what actually happened in Sumatra, which became the foundation of the story he has set in Malaya (page 315).

In 1949, while in Sumatra, Shute met the women who was to become the model for Jean Paget. He says does not think he had ever before turned to real life for an incident on which to base a novel. A Town Like Alice, he says, is a tribute to "the most gallant lady I have ever met" -- who was twenty-one, recently married, and had a six-month-old baby at the time she was taken prisoner -- and marched, carrying her baby, over 1,200 miles -- and emerged from the ordeal with her son fit and well. Time Magazine reviewShute's meeting of Mrs J. G. Geysel-Vonck, the Dutch woman who inspired the Malaya part of Jean's story, has been widely reported. It was mentioned in Time Magazine's 12 June 1950 review of The Legacy -- called "Too Good to Be True". The Time review generally pans the Australian part of the story as simply not credible (see Time Archive for complete review).

Other reflections of real lifewww.nevilshute.org sheds some light on other real people and events that inspired A Town Like Alice. In one posting, the editor makes these comments.

Captain Sugamo as a compositeIt is not clear exactly what Shute means by his reference to "the Allied War Crimes Tribunal in the year 1946". There were numerous tribunals in all theatres of World War II in Asia and the Pacific. The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE, Kyoku To Kokusai Gunji Saiban) are more commonly called the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal -- or, in Japanese, simply "Tokyo saiban" (Tokyo trials). The United States also held tribunals during and after the war in Southeast Asia. Australia, The Netherlands, France, China, and the Soviet Union also held tribunals in their jurisdictions. Twenty-eight Japanese, practically all either military or political leaders, were tried at the Tokyo tribunals. Seven were executed at Sugamo Prison on 23 December 1948. Three of the men executed at Sugamo had overseen POW camps in Southeast Asia -- Generals Doihara, Itagaki, and Kimura. The three were were found guilty of a number of charges, including Charge 54: "Ordered, authorized, and permitted inhumane treatment of Prisoners of War (POWs) and others."

Captain Sugamo's name suggests that he is a composite of all the above three generals. Yet judging from Shute's description of his military career in Southeast Asia, he was a lower-ranking officer who had spent more time in the region than Doihara, Itagaki, and Kimura combined. Sugamo not "The Tiger of Malaya"If Shute's statement about Sugamo (whatever his actual name) is correct, then he was taken into custody in Malaya (or brought to Malaya from elsewhere in the region) -- then charged, tried, convicted, and executed in Penang by a British tribunal. For after the war, Malaya remained under British control until 1948, when Britain dissolved the Malayan Union it had created in 1946, and recognized the independent Federation of Malaya -- or simply Malaysia since 1963. General Yamashita Tomoyuki (1885-1946) led the invasion of Malaya and Singapore on 8 December 1941. By 15 February 1942 "The Tiger of Malaya" had taken Singapore. Yamashita, though, was not the model for Captain Sugamo. Yamashita was sent to Manchuria and remained there until 1944, when he was put in command of the army in the Philippines. He arrived in Manila in October, on the eve of MacArthur's return invasion, surrendered in June 1945, was tried in a Manila court by the U.S. Military Commission in October and November, sentenced to death on 7 December, and hanged in Manila on 23 February 1946. Siam-Burma RailwayWork on the Siam-Burma Railway began in the fall of 1942. It was completed in sixteen months, around the spring of 1943. The construction of "Death Railway" is fictionalized in Pierre Boulle's novel Le Pont de la riviere Kwai (Paris: Rene Julliard, 1952), translation into by Xan Fielding as The Bridge on the River Kwai (1954). |

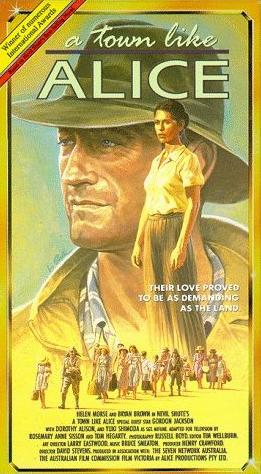

Movie and TV adaptations1956 UK movieIn 1956, "A Town Like Alice was released as a movie -- a UK production of a screenplay by the novelist Richard Mason (1919-1997) in collaboration with W.P. Lipscomb (1887-1958), a screenwriter. In the film, Jean Paget, played by Virginia McKenna, becomes a nurse. Joe Harman is played by Peter Finch. Both were English actors. The year it was released, the movie won three British Academy Awards -- Best British Actor (Peter Finch), Best British Actress (Virginia McKenna), and Best British Film (Jack Lee as director). Rape of Malaya"A Town Like Alice" was released in the United States as "Rape of Malaya" -- a title more provocative than the movie itself. The movie is generally panned as an unfaithful and (perhaps inevitably) over-simplified adaptation of the novel. The novel does not involve POW camps. The women and children are constantly on the move and minimally guarded. The number of guards decrease until, in the end, they are accompanied by only the sergeant, who has actually been fairly good to them. Then he, too dies, and Japanese officials allow the women to live in a village. The two Australian men they meet en route are not, in the novel, in POW camps. They are traveling with Japanese trucks they are responsible for keeping on the road. As survivors rather than collaborators, they are willing to help the Japanese in return for the freedom to travel with them and remain relatively healthy. Joe is able to obtain medicine, soap, and other good for the women and children only because he and his partner are minimally guarded. He knows how things work. He steals Japanese gasoline and boots to trade to Chinese merchants, who sometimes share the risk of discover by delivering the goods Jean. 1981 Australian-US TV dramaIn 1981, A Town Like Alice was adapted into a television mini-series. The joint Australian-US production was shown on "Masterpiece Theater" in the United States. Jean Paget is played by Helen Morse, a British actor, while Bryan Brown, an Australian, is Joe Harman. Names of Japanese in novel and moviesNames are often the first objects to be abused, by stereotype or distortion, when writers create characters from linguistic cultures they are not truly familiar with. Most writers of fiction in English, even those who know more than they let on about, say, Japanese names, avoid difficulties by choosing names they think their readers of English can get their English tongues. Hence the preponderance of simple names like Suzuki, Yamamoto, Keiko, Kenji, Reiko, Yuki, and a dozen or so other family and personal names that "ring a bell" with English readers. Another approach is to adopt names that are symbolic or humorous -- or to corrupt, more likely in ignorance than knowingly, actual names. Name changes in translation and moviesFew English novels related to Japan get translated into Japanese. Those that do are usually translated because they become such best sellers abroad that they can't be ignored. Good examples are James Clavell's Shogun and Michael Crichton's Rising Sun (1992). ShogunClavell thought it would be cute to base his major characters on historical figures, but to give them other names. A detailed list of all the characters and their historical equivalence is provided in the back of Henry Smith's Learning from Shogun (1980), a guide to the novel as mirror of "Japanese History and Western Fantasy". While Clavell's names are mostly authentic, some of them sound odd in the context of a fictional tale whose historical background would be familiar to all educated Japanese. Yet the Japanese translation, published in 1980 when the TV series came out, faithfully kept all of Clavell's names. The only things obviously cut were his many references to "eta" -- partly because they were incorrect, partly because the word itself is rarely tolerated in even the most authentic historical fiction in Japan. Rising SunRising Sun was a different story. Many of the Japanese names were either patently strange or so marginally authentic that the translator replaced them with clearly bona fide names.

All this -- and numerous other linguistic errors -- despite Crichton's confident acknowledgment of help from someone who "assisted ably with the Japanese text". A Town Like AliceHere is a table of the Japanese names in A Town Like Alice and how they appeared in the Japanese translation and two movie adaptations. A discussion of the changes follows the table. THE FOLLOWING TABLE IS INCOMPLETE |

|

A Town Like Alice Names of Japanese characters |

|||

| Novels [Editions] (Page number first appearance) | Movies (Actors) | ||

| 1950 English [Pan] | 2000 Japanese [NTK] | 1956 theatre film | 1981 TV series |

| Captain Yoniata (43) | Captain Koniata (Hatsuo Uda) Captain Yoniata (Hasuo Uda) |

||

| 1st sergeant (50) "the Short One" (59) | |||

| Major Nemu (60) | Major Nemu (Lim Beng Choon) |

||

| 1st corporal (62) | |||

| 2nd sergeant (63) | |||

| 2nd corporal (65) | |||

| Captain Nisui (65) | |||

| 3rd sergeant (67) gunso (76) |

|||

| Captain Sugamo (93) | Captain Sugamo (Richard Narita) |

||

| Civil Administrator (108) | |||

| Colonel Matisaka (108) | |||

| Captain Ichino (123) [replaced Sugamo] | |||

| NOT YET CONFIRMED | Japanese Sergeant Takagi (Kenji Takaki) Captain Sugaya (Tran Van Khe) Captain Yanata (Vu Ngoc Tuan) Captain Takata (Munesato Yamada) |

Sergeant Mifune (Yuki Shimoda) Japanese lieutenant (Akio Fukuwa) |

|

The names

Yoniata

"Yoniata", the first of several names of officers to appear in the story, makes no sense in Japanese, as a name or otherwise. "Yonata", the name in the 1956 movie, also lacks credibility -- though it resembles "Yoneda" or "Yonada" -- alternative readings of characters that a few people might read as "Yoneta" but not likely "Yonata".

Nemu

"Nemu" is equally opaque in Japanese as name. Only a few native speakers are likely to make any sense of these sounds as a word -- except as a component of a handful of longer family names like Nemugaki and Nemura, and place names like Nemuro.

Nisui

"Nisui" is the name of the two-stroke water radical (nisuihen), as opposed to the three-stroke water radical (sanzuihen). Otherwise it draws a total blank. The closest other words are "nisai" (two years old), and "nisei" (second generation), and "nishi" (west).

Sugamo

"Sugamo" is place name rather than a family name. As a name for the captain who later was hanged for his cruelty, is would seem to be a tongue-in-cheek allusion to Sugamo Prison, in Tokyo, where many men who were charged with war crimes were detained, then served their sentences or were executed.

"Sugaya", the name in the 1956 movie, happens to be a family name, though not a particularly common one.

Matisaka

The ear rejects even "Machisaka" (taking "ti" to be the kunrei equivalent of Hepburn "chi"). The closest names are Matsusaka and Matsusaki, both more commonly Matsuzaka and Matsuzaki.

Ichino

This is actually a possible, though unusual, family name. It is much more likely the first part of a longer name.

The sergeants

A series of sergeants appear in the story. The captains make more dramatic entrances and get names, but the the sergeants have more intimate contact with the women and children, so a sergeant's personality has a greater impact on their day to day welfare.

1st sergeant

The first sergeant is the leader of three privates (page 50), and the four soldiers are "humane and helpful" within the limits of their duty (page 51). The sergeant "spoke only a very few words of English" (page 53) but generally understands the need to rest -- and, as it turns out, bury a woman who has died. Captain Yoniata, angry not to find them on the road, "abused the sergeant for some minutes in Japanese" (page 55).

When the start out again, they find that two privates have been taken away, leaving only the sergeant and one other guard (page 56). Jean helps the sergeant, who spoke little Malay, communicate with the Malay latex tappers, and they develop a sign language the sergeant understands (page 58). She also helps him negotiate for food and shelter with the headman of a Malay village.

In private conversation with her, the headman refers to the sergeant as "the Short One" (page 59). The headman refers to Japanese soldiers generally as "the Short Ones" (page 60).

Arriving at Klang, in Major Nemu's command, the sergeant arranges for them to stay at a schoolhouse. A new guard is posted and "they never saw the friendly sergeant or the private again" (page 61).

2nd sergeant

On the trek to Port Dickson they are under the watch of a corporal (1st corporal). They stay a few days "under desultory guard" and then "the Japanese commander" puts them on the road again with two Japanese guards -- one of whom is called just "the Japanese sergeant" as before (page 63).

There appears to have been another change of guards for the trek from Seremban to Tampin, and yet another from Tampin to Malacca and back to Tampin (pages 64-65). A corporal (2nd corporal) was detailed to take them to Gemas, where they encounter Captain Nisui (page 65).

3rd sergeant

From Gemas to Kuantan they are accompanied by "a sergeant and a private as a guard" (page 67). This is the most difficult part of their trek, as they are exhausted and sick and more lives are lost. It is here in the story that we get the longest description of the guards (page 69).

As was common on this journey, they found the Japanese guards to be humane and reasonable men, uncouth in their habits and mentally far removed from western ideas, but tolerant to the weaknesses of women and deeply devoted to children. For hours the sergeant would plod along carrying one child piggyback and at the same time carrying one end of the stretcher, his rifle laid beside the resting child. There was the usual language difficulty. The women by that time were acquiring a few words of Japanese, but the only one who could talk Malay fluently was Jean, and it was she who made inquiries at the villages and sometimes acted as interpreter for the Japanese.

Learning Japanese

Having laid the foundation for the appearance of Japanese words, Shute introduces them without any fanfare -- no italics, and no glosses -- the most common devices of poor writers and insecure editors. In this scene, The Aussie whose name Jean later learns is Joe has just told her to "get fixed up with somewhere to sleep" and he'll see what he can do about getting her some medicine (page 76).

She went back to their sergeant and bowed to him because that pleased him and made things easier for them. She said, "Gunso, where yasme tonight? Children must yasme. We see headman about yasme and mishi?"

He came with her and they found the headman, and negotiated for the loan of the school building for the prisoners, and for the supply of rice for mishi.

Addressing the sergeant by his rank in Japanese may appear to be as manipulative on Jean's part as her bowing. However, both the bowing and the use of Japanese are more than instrumental: they reflect Jean's character -- her determination to relate with the sergeant as a human being on a common mission to survive. It is not a question of "friend" and "foe" but of working together in order to make the best of the worst for everyone.

3rd sergeant's death

After the chicken incident, which involves the 3rd sergeant, his subordinate is reassigned elsewhere, leaving the sergeant alone with orders to keep the party of women and children moving. The explanation for why Captain Sugamo sent only the sergeant with them is loaded with the usual stereotypes (page 95).

The same sergeant that had escorted them from Gemas was sent with them, for he also was disgraced as having shared the chickens. It was as a punishment that he was ordered to continue with them, because all prisoners are disgraceful and dishonourable creatures in the eyes of the Japanese, and to guard them and escort them is an insulting and a menial job fit only for the lowest type of man. An honourable Japanese would kill himself rather than be taken prisoner. Perhaps to emphasize this point the private soldier was taken away, so that from Kuantan onwards the sergeant was their only guard.

In one of the most moving parts of the story, the sergeant falls ill with malaria and Jean nurses him. He dies and the women tearfully bury him. In just a few lines of simple prose, Shute dramatizes the bonds that have drawn the women and the sergeant together as human beings (pages 100-101).

Freedom in captivity

Now totally unguarded, the women are not certain what to do. The villagers are kind to them, but they agree that it would be best to report what has happened to local Japanese authorities.

The Japanese Civil Administrator in the area "had been to the State University of California and spoke first-class American English" (page 108). The administrator is sympathetic with the idea of letting them stay in the village, but since they are the concern of the Army, they must see the military commanding officer, a Colonel Matisaka.

Matisaka does not wish to assign any of his soldiers to guard them so he leaves them to the Civil Administrator to do what he wants. The administrator then lets them stay in the village, where they live for the last three years of the war (pages 108-109).

Sergeant Mifune

In the 1956 movie, the sergeant gets a name -- Takaki -- which could be a family name or a personal name. As a family name, it is more commonly "Takagi".

In the 1981 TV series the "sergeants" become "Sergeant Mifune" -- as in "Toshio Mifune" (1920-1997), by then famous outside Japan not only for his Kurosawa films, but for Hollywood movies like "Hell in the Pacific" (1968), "Red Sun" (1972), "Paper Tiger" (1975), and "Midway" (1975), and for the TV series "Shogun" (1980). The theater cut of "Shogun" and the forgettable "Inchon" were released in 1981 when "Alice" aired, so "Mifune" was one of most familiar Japanese names in the world.