Paranoia invents rebirth of Yellow Peril

By William Wetherall

A review of four novels

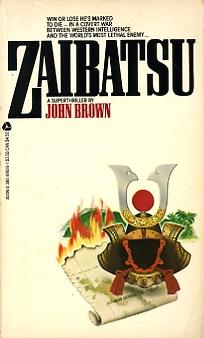

John Brown, Zaibatsu, 1983

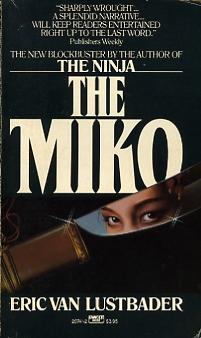

Eric van Lustbader, The Miko, 1984

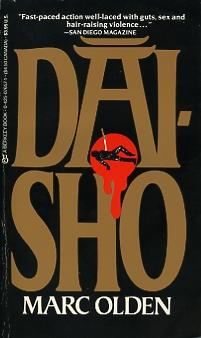

Marc Olden, Dai-Sho, 1983

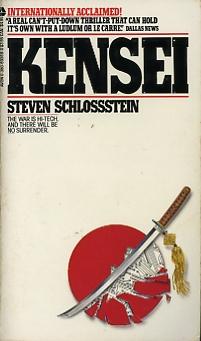

Steven Schlossstein, Kensei, 1983

A version of this article appeared in

Far Eastern Economic Review

Vol. 129, No. 30, 1 August 1985, pages 41-42

This article is a substantially revised and shortened version of 'Japanese Peril' Revived in Popular Novels as published in The Japan Times, 29 June 1985, page 7. The manscript submitted to FEER was similarly titled "Japanese peril" revived in recent popular novels. However, FEER changed "Japanese peril" to "Yellow Peril", which exaggerates the scope of the paranoia in most of the reviewed stories.

Blue paragraphs were cut from the FEER version.

Purple paragraphs were added to the FEER version.

Other phrasing may also differ from the FEER version.

A growing number of Japan watchers are concluding that nationalistic Japanese conglomerates are back. This despite the efforts of General MacArthur at the end of World War II to disband the zaibatsu.

At least four recent paperback novels reflect this growing concern with Japan's economic "invasion" of Europe, the Americas, and Pacific Asia. All are good escapes for readers with time to kill and a willingness to overlook their flaws as stories and ethnographies. But they are more instructive as examples of how fearsome Japan has become in the paranoid delusions of some western writers.

Eric Van Lustbader's The Miko (first published in 1984, now available in Fawcett Crest paperback) and Marc Olden's Dai-Sho (1983, Berkley Books) depend the most on exotic fantasy and erotic violence to carry their commonplace plots. They are also the most successful commercially, since they are better promoted (especially The Miko, which has made a number of bestseller lists), but too because Lustbader (Ninja, l980) and Olden (Giri, 1982) write with the flare of the veteran story tellers that they are.

Steven Schlossstein's Kensei (1983, Avon Books) and The Miko attempt much more than the other two titles to double as Japan travel guides. Neither succeeds, least of all Kensei, though its publisher boasts the most of its author's ostensible expertise.

John Brown's Zaibatsu (1983, Avon Books), first published in Australia, has none of the vileness and hyperbole that mar Kensei, and little of the mysticism that makes The Miko and Dai-Sho almost unreadable to realists. As a story, too, it is arguably the least inspired of the four. But in its comparative brevity, simplicity, and dullness, it does less violence to Japan's image.

What makes all four novels important as artifacts of mass culture is the common manner in which they depict Japan's conglomerates as Goliaths -- not so much because the zaibatsu are huge, as because they are run by reincarnated bushido chauvinists who believe that Japan is superior to other countries. The Bible claims that David won, but some of his modern disciples are making a living looking over the occident's collective shoulder and slinging stones at the orient's risen sun.

Steven Schlossstein Schlossstein's Kensei epitomizes the renascent "yellow peril" syndrome. Kakuei Tanaka of Lockheed scandal fame is back as Prime Minister and "in a position to fulfill his promise to . . . put Japan in a position of global power!" A Ministry of International Trade and Industry bureau chief, a Self-Defense Forces major, and the head of the planning division of "the largest industrial conglomerate in postwar Japan" believe that Japan is destined to be the "sensei" (teacher, master) rather than the "deshi"(apprentice, disciple) of the US and the USSR. The trio, all middle-aged products of the elitist University of Tokyo (where Schlossstein studied as a graduate student), conspire to make Japan militarily powerful enough to refuse to renew the Security Treaty with the US, and to force the USSR to return the Kurile islands, all by 15 May 1985. If not, they will atomize twelve major cities around the world, including Tokyo. But the Japanese are unable to develop the "256K optical chips" needed to guide the multiple warheads that they have secretely developed. So some are stolen from their American developer's Silicon Valley plant, by a Japanese disguised as a Vietnamese refugee janitor. All Asians look alike. Schlossstein, who laments the decline in American values which nurture creativity and qualtiy, seems to be saying that Americans had better shape up or be defeated by what he calls Japan's "deadly traingle"--calculation, domination, elimination. He has his American hero jam a finger in a MITI bureaucrat's chest on behalf of himself and other Americans who would like to get tough with the Japan. A PhD Japanologist with "doll-like features" (no, she is not oriental) gives Kensei's blue-eyed blond hero with "an easy smile" a crash course on Japan. Schlossstein condenses all that he wants his reader to know about the Japanese mind into the mnemonic acronym CHIPS, for Cultural superiority, Hierarchy, Insularity, Perseverance, and the need to become the world's Sensei. This is strong stuff. Even when bearing heavy messages like these, entertainment fiction is supposed to be fun. Sax Rohmer, too, may have been obsessed with the notion that Asia was the spawning ground of satanic megalomaniacs like Fu Manchu, but his stories never reeked of the overt hostility that drips from Schlossstein's pen. |

Eric van Lustbader Semiconductors that America has and Japan needs, and Japan's desire to be self-sufficient if not dominant, are also the issues of The Miko. The "half-Caucasian, half-Oriental" hero of Lustbader's previous novel, The Ninja, returns to save Japan and America from the evils of Soviet communism. A US hi-tech firm with the "goods", and a Japanese company with the "wherewithall" to produce the US firm's non-volatile RAM chips at the right price, are negotiating a merger. The Japanese company is a subsidiary of a large petrochemical corporation, which is owned by a development bank that is chaired by its founder, a kamikaze survivor and ex MITI vice-minister who despises foreigners generally and "half-breeds" particularly. Meanwhile, a patriotic ninja master is guarding the plans for Tenchi, a super-secret project that involves the petrochemical company and would make Japan forever independent of both the US and the USSR. The intelligence agencies of both countries (and China) are on to it, of course, and their spies will stop at nothing to sabotage it and thus keep Japan under alien thumbs. The Miko is the most sympathetic to the desire of some Japanese to be rid of outside influences. But Lustbader's message seems to be the too familiar canard, that a non-Asian needs at least a drop of Asian blood in the veins to really understand and get along with the Japanese. The Miko's conveniently mixed-blood hero, as bilingual and bicultural mediator for the US firm, coaches his bull-headed boss in the finer arts of tiptoeing through the non-tariff minefields. But this is merely Lustbader's gimmick to heighten the reader's cathartic illusion that vicariously enjoying grisly murders and suicides, interspersed with gruesome sex, is educational. Unfortunately, such possibly good advice as "Stop thinking with your Western ego and try a little acceptance" is nullified by nonsense such as "There were no exact street addresses in Tokyo, a peculiarity that nonplussed all foreign visitors", and "In the East . . . traditionally death means nothing". |

Marc Olden The hero of Olden's Dai-Sho is an ex-New York cop with a slight limp and a mean cane who takes on the demented might of a Japanese industrial -espionage ring run by a wealthy potentate who had been convicted as a war criminal but beat the hangman. The ring is "one of Japan's most efficient terrorist and espionage units", and it is run with the help of "unlimited funds from right-wing businessmen." The potentate's worldwide dirty tricks have earned him the reputation of being "Japan's most effective spymaster" since medieval times. The hero, not a Japanologist, can't understand why the Tokyo government doesn't sanction the industrialist's activities. An old Japan hand sets his mystified compatriot straight: industrial espionage "is not, repeat, not a crime" in Japan, but merely part of the country's defense. |

John Brown Brown's Zaibatsu shifts the theater of Japanese design on the world to Southeast Asia. It's hero is a New Guinean of Anglo-Australian ancestry residing in Switzerland who returns to New Guinea to look into the murder of his brother. The suspect is "the wealthiest and most powerful man in Japan", who is the head of a zaibatsu that "doesn't have one particular company name, but [is] still the biggest of them all." An advertising blurb claims that the zaibatsu head "will sacrifice anything or anybody to the fanatic dream of a new Japanese empire", but the hype outdoes the story. While the zaibatsu head does try to cause uprisings, revolts, and coup d'etats in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea "to develop the resources of the resultant nation in an economic union with Japanese interests", he is "too much of a man" to have murdered the hero's brother, who had been his friend and collaborator. |

All four novels leave the impression that Japan's corporate executives are more ethnocentric than their outlander counterparts. The authors of The Miko and Zaibatsu, though given to stereotypes and caricatures, are truer to the traditions of the genre in the sense that they make at least token efforts to humanize their villains. Wherease the bad guys in Dai-Sho are unredeemable embodiments of diabolical evil, while Kensei appears to almost purposely racialist.

It is anyone's guess who reads such novels, muchless how their thinking is shaped by them. Most studies of pornography are inconclusive on the question of whether smut encourages sexual crimes. But analyses of popular novels tend to show some correspondence between their content and prevailing images of other peoples and countries.

Japanese fiction, too, is full of misunderstanding and racism. Even so, one should like potboilers in English about Japan to be written by people with more knowledge of its culture and society than Lustbader, Olden, and Brown, and with more respect than Scholssstein.