|

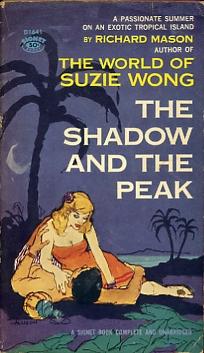

The Shadow and the Peak

1959 Signet paperback (US)

|

|

|

The Passionate Summer

1960 Fontana paperback (UK)

(Formerly published as

'The Shadow & the Peak')

|

|

Richard Mason

The Shadow and the Peak

Hardcover editions

London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1959

326 pages, hardcover

London: The Book Club, 1949

256 pages, hardcover

New York: Macmillan Company, 1950

298 pages, hardcover

Paperback editions

New York: Signet Books, 1959

240 pages, paperback (D1641)

The Passionate Summer

London: Fontana Books (Collins), 1958

253 pages, paperback (283)

[Second impression 1960]

Mason's least read novel

Published in 1949, The Shadow and the Peak was the source of the story for the 1958 movie "The Passionate Summer" -- hence the title of the edition Fontana Books put out in 1958, shown here in a 1960 second printing. Signet Books brought its paperback, with the original title, in 1959.

All indications are that The Shadow and the Peak, Mason's second novel, did not do well in its hardcover edition, coming as it did on the heels of his very popular first novel, The Wind Cannot Read. The paperback editions came out only when the film was released, a decade later, and even they do not seem to have attracted many readers.

That the novel didn't get a better reception is a shame, though, for it is well crafted if controversely written.

A passionate summer

The covers of both the Fontana and Signet editions advertise that Mason is the author of The World of Suzie Wong, which had come out in 1957, the year before "The Passionate Summer" was released. The play based on The World of Suzie Wong also began to run in 1958. The movie based on The Wind Cannot Read also came out in 1958, and by 1960, Robert Lomax had become an American in the movie version of Suzie.

So the late 1950s and early 1960s were good years to promote anything with "Richard Mason" and "Suzie Wong" on it. The cover of the Signet edition of The Shadow and the Peak actually shows "Suzie Wong" larger than "Richard Mason".

Premonitions of Richard Lomax

The Shadow and the Peak is of interest only because it features an Englishman who has come to exotic Jamaica for essentially the same reasons Robert Lomax came to Hong Kong -- to get away from personal problems in England.

The cover of the Signet paperback invites the reader to enjoy "a passionate summer on an exotic tropical island" -- and the blurbs on the back flesh this out, so to speak.

|

ISLAND OF

DESIRE

Douglas Lockwood came to Jamaica to recover from the heartbreak of a messy divorce. But instead of peace he found passion, and three beautiful and disturbing women who threatened to turn the island idyll into a summer storm.

There was

Judy -- the beautiful airline hostess who seemed to return his affection -- when she wasn't chasing her married lover

Silvia -- an uncontrollable young girl, madly in love with Lockwood

Mrs. Pawley -- his boss' sex-starved wife, who pursued him openly

|

Chinese lover in Penang

Jamaica is not as far from Asia and the Pacific War as one would think. Lockwood had been in India during the war (page 41, Fontana edition). While in India he had acquired a small wooden elephant, and it meant enough to him that he had packed it in his suitcase when going to Jamaica.

He had had other experiences in Malaya (page 62).

In Malaya, when the war had ended, he had believed that his love for [his wife] Caroline had died with his love for the life she represented; he had returned home uneasily from the arms of a Chinese whore in Penang. When he found that her own love had expired more certainly, he was overcome with a fresh desire for her.

This thread is further developed in Lockwood's thoughts about Judy, a suicidal seductress he finds irresistible (page 69)

[He] wondered what he ought to do about Judy. He thought about her long, slender legs and her quick, frank smile. Probably she was very promiscuous and would let him make love to her, and afterwards he would regret it because she would go away. He was not good at making love to people and not falling in love with them; he was more like a woman in that way. He had even got upset over that Chinese girl in Penang, who had loved him so much on account of his nice red tins of Craven "A" cigarettes which could be sold for eight dollars a tin, and he hadn't even been able to talk to her except in mime. He could fall in love in a brothel; thought unfortunately he couldn't fall out of love with Caroline in one or he'd have tried it long ago. Perhaps Judy would help him fall out of love with Caroline a bit. It was a good excuse, anyhow . . . .

A racial zoo

Race and race relations figure strongly in Mason's novels. The Shadow and the Peak is full of "negroes" -- also called "coloured people". Most are servants and caretakers. Some have names like "Joe".

Since Jamaicans come in all colors, Mason describes Silvia, who was only twelve but "looked much older than most girls of that age in England", as "white Jamaican" (page 37).

An elderly "Jewish-looking man with a stoop and a monocle hanging on a black ribbon around his neck" is dubbed just "the Jew" in later references (pages 99-100).

At a bar he talks with "a mulatto with an unshaven chin" (page 109).

The chap called him Mr. Lockwood. Douglas asked him how he knew his name was Lockwood, and the chap said that although he was a poor nigger he knew all the illustrious white men in Jamaica. It was the first time Douglas had heard a mulatto call himself a poor nigger.

Interesting mixtureAfter swimming with Judy, her body brown and slim, they had tea (page 110).

"I don't know anything about you," he told Judy."

"Except that I rush about after men and commit suicide."

"I mean before that. Where were you born? I can't fit you into a background."

"I'm one of those people without backgrounds." She smiled and pushed away her hair. "Cities throw us up. We end in brothels in China."

Later they have dinner at a Chinese place (page 113).

The food was poor and wasn't Chinese at all, and there weren't even chopsticks to show off with. It was served by a girl of nine who was mixed Negro and Chinese, with probably some Indian thrown in. It was an interesting mixture.

Leper rumors

Early in the story, Pawley, the master of the school where Lockwood is teaching receives a letter claiming that the grandfather of one of Lockwood's students died in a leper colony. The letter writer contends that the John Cooper "is not fit to mix with other human beings" (page 54).

Lockwood defends the boy, who is examined and shows no signs of having leprosy, but the rumor does not go away. A woman at a cocktail party asks Lockwood if it was true. He dispels the rumor then steals away from people's eyes. The narrator tells us "The leprosy story had made him furious" (page 102). Later the schoolmaster receives another letter, admonishing him for not yet taking action. Pawley speculates that the letter is from "someone who objects to a coloured boy being at the school (page 121)

It sounds from the language as if a coloured person had written it," Douglas said. "Or at any rate a mulatto."

"Probably a mulatto," Pawley said. "They'd be the first to find fault with John -- for being blacker than themselves."

Lockwood visit's John's mother and in time he learns who has written the letters and why (pages 122-123). That both of John's maternal grandparents had leprosy was true enough, but his own mother was never infected. In one of the more interesting subplots of the novel, the rumors continue to spread, until John himself hears them and wonders if he has the disease (pages 144-145).

Mixed mirth and hairy humor

Lockwood and Judy, in a good mood after seeing an American movie, have supper at "the Chinese place with the Chinese-Indian-Negress waitress" (pages 158-159).

"Perhaps she isn't too young for you, after all," Judy said. "You know what girls are in the tropics. And she obviously wants some white blood for the family collection."

"I'd like to see her have a baby with a Russian-Eskimo-Javanese."

"Have you ever met one of those?"

"Yes -- except it wasn't Eskimo, it was Icelandic. He was a man who lived in a boarding-house in London and studied law. He kept feeling nostalgic, only it was rather confusing because he never quite knew where he was nostalgic for. He died."

"Of nostalgia?"

"No; he caught pneumonia in the English winter. It was probably the Javanese part of him that let him down."

Judy laughed and said, "How wonderful to be talking rubbish again! Louis never talks rubbish. I'm so glad he's gone."

"He must be in Cuba by now."

"I wonder what a Jewish-Hungarian-Cuban would be like," she said."

"A Jewish-Hungarian-Hairy-Ainu-of-Japan would be better," Douglas saids. "Then there'd be no need for gum-arabic."

"What a splendid idea -- shall we send him a cable about it?"

"He might take it seriously," Douglas said. "Think of all the hair there'd be in the next generation. People would be committing suicide all over the shop."

Better than average story-telling

The Shadow and the Peak is full of life and local color. The characters are fairly credible. The adults are passionate but not in the manner promised by the sensational cover blurbs.

Mason is a skillful structuralist. Some of the smallest of dropped threads and later picked up.

I get the impression that Mason has infused Douglas Lockwood, a fairly conscientious and likable school teacher, with the slightly warped wit of British national like himself, who has seen so much of world, and life, that he finds himself nostalgic for everywhere and nowhere.

|