Amerippon or Nipponica?

Conspiracy -- or nature taking its course?

By William Wetherall

A version of this article appeared as

"'Samurai Strategy' good for straight pulp fix" in

The Japan Times, 7 January 1989, page 14

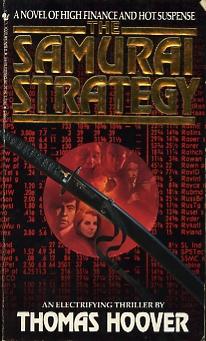

Thomas Hoover Former international consultant turned novelist, Thomas Hoover, shares Eric Van Lustbader's (The Ninja, Sirens, Black Heart, The Miko, Jian, Shan, Zero) and Marc Olden's (Black Samurai, Giri, Dai-Sho, Gaijin, Oni) fascination for the sword, bushido, Sun Tzu, Miyamato Musashi, Zen, harmony, and non-verbal electricity. His knowledge of Japan, as reflected in his conscious efforts to educate the reader, is also as flawed as that of most other writers of Shogunesque thrillers. The Samurai Strategy is set in the imminent future. Matsuo Noda, an ex MITI (Ministry of International Trade and Industry) potentate, runs a scam on the Imperial Family and tries to buy the United States in a bid to become the shogun of the world. Noda "came from ancient samurai stock -- fittingly, perhaps, since the bureaucrats of modern Japan are mostly of that class," Hoover explains. At the end of the Pacific War, Noda vowed to continue the struggle "for the eternal cause of loyalty to the emperor." Noda was running MITI when it "ate the American semiconductor industry." After heading the Japan Development Bank, he set up an investment consulting company called Nippon, Inc., later renamed Dai Nippon, International. Through DAI he attempts to precipitate a "Black November" that will make Meltdown Monday (Monday Massacre) of October 1987 look like just "the warm up . . . a nostalgia item." Noda hires lawyer Matthew Walton to do his dirty work legally. Walton, who specializes in defending corporations against hostile takeovers, also collects Japanese swords and fancies himself "a sort of American ronin, a wandering samurai" (learn Japanese as you read). To revive pride in the divine origins of Japan's "monoracial state", Noda steals one of Walton's swords, plants it in the Inland Sea, and hires a marine scientist to "discover" the sacred imperial sword that is said to have gone to the bottom with the child emperor Antoku in the 12th century during the Heike war. Tamara Richardson is Hoover's unusual "Japanese" female name for a staunch American critic of lackadaisical management in U,S. companies. She is also the bilingual, bicultural, biracial intermediary that has come to be inevitable in such intertribal fiction. "Where'd she come from? American, sure, but no way could she have been corn-fed Midwest like her surname," narrator Walton observes. "The answer was, she had a slightly more exotic, and probably painful, history than most of us." Richardson grew up an orphaned daughter of a Japanese woman and an American man, both of unspecified race. She was adopted by an American military couple who loved Japan so much they sent her to a Japanese school instead of the "army brat" school on base. The novel's tragic non-hero is Kenji (yes, another Kenji) Asano, a powerful bicultural MITI official with an MIT PhD who "was nothing like the typical sexless, oblique Japanese businessman. He had a superb body . . . a sense of style: the power look." Asano enters the story ambivalently on Noda's side but departs it clearly against him. "Our country has a monarchy older than Rome, a heritage of literature, art, aesthetics, equal to anything in the West," Asano explains to Richardson (though really the reader, for she must already know this). Then he adds (showing his creator's ignorance rather than his own): "We've never had any colonies, any raw materials besides air and water. All we do have is a willingness to work and save -- the one natural resource running short in the West." When Asano realizes that Noda has been manipulating him and MITI, he is willing to embarrass his own ministry, and risk his career, to stop Noda's incursions into American industry. He sees "professional seppuku" as the only way of repaying his debt to America. Akira Mori, another of Hoover's unusually named women, is Japan's sexiest money analyst, an avant-garde woman on the outside, a racial supremacist on the inside. "Yamatoists believe, rightly," she explains to Richardson, "that a temporary eclipse of our Japanese minzoku was brought about by the American occupation, whose imposed constitution and educational system were acts of racial revenge against Japan." Noda and Mori tell Richardson that her biological mother had been a descendant of the Fujiwara clan, and even Asano helps persuade her to fulfill her genetic role as a defender of the imperial tradition. As Mori comes out of her Yamatoist closet, however, she proves to be an anti-shogunist who wants to restore the emperor's divinity but protect him from manipulation by power mongers like Noda. By the end of the story her only concern is to cover up his archaeological fraud which, if exposed, would nip her racial renaissance in the bud. The Samurai Strategy was published in June this year as a first-edition paperback for martial arts mainliners in the United States who need a straight pulp fiction fix in an election year that may still see Japan become an issue. Hoover, though, offers his worst-scenario fictional forecast in the spirit that "you look into the crystal ball and hope what you see never happens." Hoover raises, but does not answer, the question of the century for people who are seriously concerned about Japan-America relations. Walton's closest confident drawls: "Is the idea of turning our [U.S.] industrial base into a packaging operation for imports some kind of conspiracy, or is it just nature takin' its course?" Only as a decoy in his quest for personal power does Noda really believe that, if they join together "the peoples of Japan and America can achieve insurmountable strength." Such appeals to the trendy Pax Amerippon (joint hegemony) ideology attract Walton, Richardson, and others in the United States -- who are thus co-opted until they realize the true aim of the "massive Japanese-American consortium" that Noda wants to call "Nipponica" because it has "an interesting ring to it." Hoover comes closer than other Japan-peril writers to the heart of the academic and journalistic debate about the apparent decline of the United States and the doubtful rise of Japan into the hegemony vacuum. He seems to be warning that Americans had better become alert samurai like Walton, who uses his cunning attorney powers to turn the tables on Noda and put all those billions of "homeless" Japanese savings in U.S. hands, so that Americans can rebuild their weakened industries, and keep them too. |