Summer of the Big Bachi

The debut of Mas "Easy Rawlins" Arai

By William Wetherall

First posted 3 September 2006

Last updated 4 October 2006

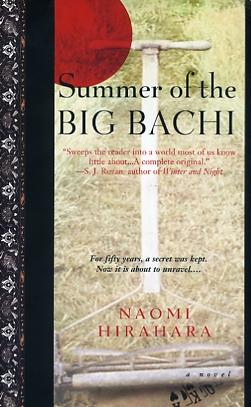

Naomi Hirahara Naomi Hirahara's debut novel is not bad. The story line is sound, and the narrative stands midscale between Walter Mosley and a writing student who has missed a few classes -- which means it's pretty good. Summer of the Big Bachi comes so close to being a much better work that I felt compelled to show, in some detail, where I think it falls short. Bear in mind that all of the following comments are applicable to all English fiction being written today. Unlike Hirahara's novel, most other stories I read are fatally flawed by structural weaknesses beyond the scope of this critique. Mentors and motivesAsian Pop writer Martin Wong, in his SFGate (San Francisco Chronicle) review of Summer of the Big Bachi, apparently attended its launch at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, at which Hirahara reportedly talked about her literary models (SFGate, 16 April 2004).

YappariMy first response to reading Wong's review, after I had finished Summer of the Big Bachi, was -- "Yappa!" You see, I have been living in Japan most of my life, and I am now more likely to speak Japanese than English. Many of my waking hours and some of my dreams are in Japanese. My English is as strewn with Japanese words as some of Hirayama's characters, especially when I visit the United States, where I was born and raised. Sometimes it's just too mendokusai to speak only English. Come to think of it, though, my brain doesn't consider it fushigi that words I once consciously associated only with Japanese now flow into my English so spontaneously that, when in America, I'm not even aware of how mechakucha my speaking becomes -- until I get a strange look from someone who trips over my reflexive hais, gomens, and shitsureis, and queries like "You gotta meishi?" and "Nande?" Mosley + Berlitz + My HeritageAnyway, I thought as much. I suspected there was a little Mosley, and a bigger heritage teacher, in Hirahara. Being a Mosley fan, I was struck by the resemblance between Masao "Mas" Arai and Ezekiel "Easy" Porterhouse Rawlins. The personalities of the two men, and the ambiances of their worlds, are similar. And both men are compelled to be amateur detectives of the categorically "reluctant" or "unwilling" sort who actually thrive on dangerous involvements. I was also struck -- often distracted -- by Hirahara's language and culture lessons as she strives to be a heritage teacher as much as a story teller. In this and other stylistic respects, she is no Walter Mosley -- who rarely breaks into his highly dramatic and minimalist narratives to lecture readers about something he could have shown them -- or simply left out because it doesn't contribute to character, plot, or genuine ambiance. Wong's insinuationsWong wrapped up his review with an assessment of the reception that awaited Summer of the Big Bachi (SFGate).

Wong seems to be making three insinuations. (1) "Literary-minded" people would not ordinarily read the sort of fiction that Hirahara writes. (2) "Asian Americans" with literary minds will buy such fiction only in order to support an Asian American author. (3) "Literary-minded Asian Americans" will not have had an opportunity to read such a mystery before, because Hirahara is the first to write one. QualificationsAll three insinuations invite qualification. (1) Some people who don't habitually read genre mysteries are known to read Walter Mosley, for example, because he crafts his stories as literature -- never mind whether they are marketed as "fiction" or "contemporary literature", or whether he would admit that he is an artist. (2) Some "literary-minded Asian Americans" may be genuinely curious about the literary quality of what Hirahara has written -- regardless of the fact that her stories happen to be mysteries and she happens to be an Asian American. (3) A number of Japanese Americans have written mysteries, including the very prolific and pulpy Milton K. Ozaki (1913-1989), who also wrote as Robert O. Saber. More recently we have seen the somewhat clunky, short-lived efforts of Dale Furutani (b1946). Bachi for linguistic license?Some titles never appear in a story, and some appear several times. Most longer titles appear no more than once. The title of this novel appears just once, as "summer of the big bachi" (page 117) -- though "bachi" is not italicized in the title. Though "bachi" is less common in Japanese today than it was in the recent past, some expressions are still in general use. When it stands alone, the character ”± is read "batsu" (a "kan'on" or "Han pronunciation") when meaning just punishment, but "bachi" (an older "go'on" or "wu pronunciation") when meaning retribution by the gods that be. In compounds, though, it is usually read "batsu" -- as in "tenbatsu" (“V”± punishment brought about by heaven) and "myobatsu" (–»”± punishment brought about by unseen machinations of the gods). Basically, then, "bachi" means "divine retribution" for having done something wrong. While most older native speakers will have read if not heard bookish expressions like "bachi wa me no mae" (punishment is right before your eyes) and "tenbatsu tekimen" (divine retribution is imminent), no one goes around saying such things. If native speakers of any age today say "bachi", it will be in expressions that mildly chide or strongly rebuke someone for doing something wrong. Someone may say "Bachi ga ataru yo!" (It's gonna come back to you!) to a friend or colleague involved in an illicit romance. Or a parent may say "Kono bachiatari me!" (You sinful little fool!) when scolding a child for shoplifting or whatever. The short preface to Summer of the Big Bachi introduces the idea of "bachi" and ends with the observation that "Mas was still around, waiting for bachi to strike at any second" (page 2). This reflects the verbal phrase "bachi ga ataru" (bachi strikes), whereas the noun "bachiatari" means a situation, behavior, or even a person that invites or deserves bachi. Words in one language enter another because influential speakers or writers use them and they catch on. "Bachi" and "batsu" entered Japanese as Chinese words. Numerous English words enter Japanese and Chinese for no good reason except that someone began using them and they spread. I rather doubt that Summer of the Big Bachi will get enough circulation to attract the attention of English lexicographers. Who knows, though. The inclusion of "bachi" in a future edition of OED may be the price the English language has to pay for Hirahara's license. It would be in good company, though, since most of OED's entries originated in other languages. The storyThe story is about the life of Mas Arai -- his deceased wife Chizuko and their living daughter Mari, his friends and neighbors, his truck, tools, clients and gardens, other people and plants he encounters, and through all this his somewhat cantankerous and otherwise less than magnetic character. The plot around which the story is told concerns what happened to Mas and a few of his buddies in Hiroshima during the war. The following remark appears before the preface.

Back cover blurbThe blurb on the back cover states that by the end of the summer a man named Joji Haneda will be dead. It also alludes to "powerful secrets" Mas has been keeping -- secrets "about three friends long ago, about two lives entwined, and about what really happened when the bomb fell on Hiroshima in August 1945 . . . ." The back cover states that "For Mas, a life of sin is catching up to him. And now "bachi -- the spirit of retribution -- is knocking on his door. Preface and Chapter OneThe preface expands on the meaning of "bachi", says that Joji Haneda was dead, and ends with the remark that, "While Joji had escaped, Mas was still around, waiting for bachi to strike at any second. Chapter One is set in the lawnmower shop of one of Mas's friends, who figures in the story. The chapter begins with a couple of pages of mostly undramatized commentary about the men in the shop and Mas's deceased wife and their daughter. The narrative picks up dramatic speed with conversation between the men in the shop. Mas then becomes aware of the presence of another man. The stranger identifies himself as Shuji Nakane, an investigator. Nakane thinks that Joji Haneda is alive and in America, and that Mas and his friends might know his whereabouts. Nakane exits the shop, leaving Mas with his friends and his thoughts. Having thus baited the hook, Hirayama sets it with this closing paragraph.

This sounds more like the closing of an early episode in a matinee serial or soap opera, than of a chapter in a well-crafted mystery. A few other chapters similarly end with anti-literary attempts to build suspense. Fortunately, though, the pacing is good, and the suspense builds despite the occasionally prosaic writing. The writingHirahara is not a bad writer. Structurally, Summer of the Big Bachi bears its narrative weight fairly easily. The story is sufficiently captivating and plausible. As a protagonist, Mas Arai is interesting though he could and should be more endearing. The main problem with Hirahara's writing is the way she handles dialog and dialect, the intrusion of vocabulary glosses, and sometimes irrelevant social commentary -- as though she set out to make the story a vehicle for heritage lessons and more. She also seems to like convoluted similes and horribly mixed metaphors -- which I will not discuss here, as they are easily recognized. Language confusionIt is not always clear whether English or Japanese is being spoken. The sequence of dialog between Nakane and Mas, in Chapter One, is the first example (pages 7-9).

Hirahara is avoiding the hard work of writing a dialog that takes place in two languages. The reader hears standard English from the mouth of a man who is speaking in Japanese -- vaguely signaled by "Haneda Joji" rather than "Joji Haneda" -- but non-standard English from the mouth of a man who is bilingual enough to understand the Japanese, but who in this scene prefers to speak English. In some other scenes, too, Hirahara's double standard of representing Japanese and English speech results in confusion as to what languages are being spoken. DialectSome of Hirahara's characters speak forms of English flavored by unconventional pronunciation, usage, and grammar. Here I will comment only on pronunciation. Hirahara show non-standard pronunciations in several lways.

Presumably Mas and a couple of his kibei friends were very young when they went to Japan, where they spoke mostly Japanese. Presumably they returned to America able to speak mostly the sort of English that Hirahara puts into their mouths. Some of the vernacular forms, and most of su / zu forms, come only from the mouths of Mas and his friends. But their use of such forms is haphazard. I get the impression that Hirahara has identified only a couple of conspicuous dialect traits and then exaggerated them. The su / zu forms are clearly intended to mark the vestiges of certain Japanese habits of speech on English. But Hirahara has reduced such habits to caricatures. The word she most frequently uses to signal a "kibei" accent seemzu tsu bee "knowsu" -- butto who knowzu? Characters from JapanHaving gone to so much trouble to concoct a kibei dialect, why does Hirahara not color the speech of characters who were born and raised in Japan and came to the United States as adults? These characters speak either in Japanese presented in idiomatic English, or in fairly good if not flawless English, showing few if any signs of the traits most native speakers of Japanese are likely to exhibit when speaking English as a second language. The first words we hear from Junko Kakita are "You're Joji's friend, desho? I had heard that you'd be coming" (page 34). Not the native colloquial "I heard you were coming" but an extremely correct "I had heard that you'd be coming". Is this intentional? The next time she speaks the narration says (page 36): '"There," she said with a slight accent. "You check it."' Even while she is drinking she is saying things like (page 38): "I thought the whole point of him coming to Los Angeles was to spend more time with me. But I could tell that it was for something else." This from the mouth of an alcoholic who doesn't have a green card and plans to go back to Japan. None of the characters Mas would think were "straight from Japan" seem to have any problems speaking English. You would think at last one of them would fumble more articles, plurals, number agreement, prepositions, passives, causatives, perfects, modals, whatever. Or that one would show signs of not yet having mastered certain English sounds that continue to perplex some native speakers of Japanese who learn English as a second language -- nebaa maindo, janku huudo, wam mairu -- whatever. I am not saying that Hirahara should have attempted to be more realistic. In fact, I strongly learn toward the school which holds that stories are better off without linguistic affectations. Unless the writer has a pitch perfect ear and complete control of a readable orthography with which to represent authentic dialect -- I am all for keeping speech within the parameters of the mainstream dialect. The difficulties of representing authentic speech are compounded when two languages come together in what amounts to a pidgin or hybrid. Summer of the Big Bachi would have read much better if Hirahara had not so extremely imposed her contrived "su / zu" dialect on Mas and his friends. Kibei stereotypesHirahara seems to have stereotyped kibei as linguistically challenged. Yet many kibei finished junior high school or even high school in the United States before going to Japan. And many who went to Japan when younger also returned to America with no serious loss of their native English ability. Numerous kibei who returned to America before Pearl Harbor were sufficiently bilingual to teach Japanese in wartime language schools, and serve in the Pacific during the war, not a few of them in military intelligence, and in Japan during the occupation as high level translators and interpretors. I have met and gotten to know several such Americans. Pronunciation lessonsHirahara gives a few pronunciation lessons, and the intent is often unclear. HiroshimaMas and Stinky Yoshimoto, another of Mas's gardener friends, are speaking in the presence of Nakane, about where Mas had known Haneda (page 7).

Here it is not clear whether Stinky is mocking or correcting Mas, or enunciating Hiroshima this way for another reason. For what it's worth, the standard Japanese pronunciation is "hi-RO-SHI-MA" -- with a fall in pitch after RO-SHI-MA -- e.g., hi-RO-SHI-MA-ken. MariMas is talking with Mrs. Witt (page 45).

This works well. TsukemonoMas is in a liquor store. The propritor, Frank, begins talking about Mr. Yano, who had owned the store next door, until he was shot for fifty dollars. The Yanos sold pickled plums and dried seaweed (page 131). "He had some nasty stuff in there -- long pickles in this mean brown stinkin' stuff. What do you call it?" The pickle = tsukemono exchange is obviously a food and language lesson. It is also another dramatization of mangled pronunciation by people who are not of Japanese descent. MusumeFrank is described as a "black man with grizzled hair" (page 130). After the pickle remarks, he trys to recall what Mr. Yano had called Mas's daughter (page 131).

The daughter = musume routine is also a vocabulary drill. But the intent of "mu-SU-me" is vague. It is not contrasted with anything. Mas is shown to be irritated by Frank's talk about Yano, but it is not clear why he didn't like the musume reference to Mari. For what it's worth, the standard pronunciation of musume is mu-SU-ME, with a fall in pitch after SU-ME -- e.g., mu-SU-ME no na-MA-E ga MA-ri da. ItalicsHirahara italicizes words she regards as "Japanese" -- meaning words from Japanese that are not yet in major English dictionaries. Such linguistic discrimination is common in prose -- but has no place in literature. Here are a few examples to show the nature of problem.

Hirahara does not italicize "ramen" or "bonsai" because they are in Random House and many other English dictionaries. In other words, Hirahara is thinking like an editor who follows rules having nothing to do with natural language, and everything to do with the politics of publication. She is not thinking like a story teller, but like an editor who is duty bound to abide by a style manual which dictates that words not in English dictionaries can be admitted to English texts only if visaed by italics. Words are statelessHowever, words that spontaneously issue from the mouth of any character, or which appear without ulterior purpose in a narrative, have no nationality and need no passport. Guileless speakers and narrators do not pronounce or think in italics. Yet numerous italicized words leap off the pages of Summer of the Big Bachi, demanding attention they never get in the world Hirahara claims to be revealing. In the natural world, "You going to get big bachi" (page 4) would be simply "You going to get big bachi." "Masao-san" (page 4) would become just "Masao-san" or even "Masao san" -- if in fact Mas's wife would actually address him this way. "Joji-san" (page 8) would similarly be just "Joji-san" or "Joji san" -- if in fact Nakane, who did not know Haneda, would address him by his personal name. Later, when confronting Mas about his denial of friendship with Joji, Nakane refers to him as "Haneda-san (page 47). "Hardly anyone there, ne" and "You're Joji's friend, desho" are natural -- ne (page 6) and desho (page 34) exotify these expressions in ways their speakers did not intend, and hence they are unnatural. "How did you hear about us? Terebi?" is likewise natural -- whereas "How did you hear about us? Terebi?" (page 30) misrepresents the intentions of the speaker. Vocabulary lessonsAnother fault of Hirahara's story telling, which puts her in the same class as other authors who have jumped from informational writing to literature, is her desire to teach readers what words mean. This desire motivates her to commit two literary sins: (1) she exotifies her favorite "Japanese" or "heritage" words with italics, and (2) she interrupts natural dialog and dramatic narrative in order to insert definitions.

As a result, Summer of the Big Bachi is littered with expressions like these.

Most of the above lines are unnatural. People generally don't talk this way, unless they are giving language lessons. Kokoro and chantoHirahara has very consciously woven a sizeable Japanese-English dictionary into the story. At times she even defines two words in the same paragraph, using the same formula -- as in the following passage, where Mas is recalling the first impressions he had of his now deceased wife (page 127).

This is not Mas speaking, nor is it the voice of a narrator who stays within Mas's thoughts. Rather it is the voice Hirahara, very intentionally and undramatically injecting a couple of language and heritage lessons into the narrative. GenkanPractically all homes and apartments -- and still many smaller schools, clinics, companies, and restaurants -- have an area right inside the entrance, which is part of the larger vestibule, where people leave their shoes before stepping up onto the floor and usually but not necessarily into slippers if not another form of inside footwear. Hirahara knows this, of course. Yet in her rush to be clever, she writes this (page 111).

On the same page, she is busy mentioning kotatsu, furoshiki, unchi, hoppeta, and butsudan -- all italicized, and butsudan with a big B. Inoshishi -- originalSometimes the lesson gets downright laborious (pages 74-75).

Inoshishi -- RewriteEverything should be dramatized without the clumsy "Year of the Dragon" lesson -- and with more attention to the warmth of Mas's memories of Akemi.

This is a bit longer because it absorbs another part where Hirahara suggests there were feelings between Masao and Akemi in Hiroshima. Shochu -- OriginalHirahara glosses Japanese words many ways, sometimes very indirectly -- which, if you have to gloss a word, is the way to do it. But one has to be careful to obey the dramatic rules. Hirahara breaks several rules in the following scene, in which Mas meets Junko Kakita, Joji's girlfriend, at her North Hollywood apartment (pages 36-38).

Shochu -- RewriteThe narrator should reveal only what Mas can actually see and not speculate about details that are beyond his perception. Mas needs to be more curious and responsive, and his feelings should be dramatized.

Nothing needs to be said about shochu. Why? Junko knows what it is, and Mas knows what it is. The reader either knows what it is or can guess that it's something alcoholic. Calling it "yam wine" even once, much less repeatedly, contributes nothing to the story and does not really tell the uninitiated reader what shochu is. Let words rip from the lipsThe problem of using Japanese words in English literature has three simple solutions: (1) don't use any words that are not absolutely required by the story itself, (2) deliver the words as though they had every right to be there, without commentary, and without exceptualizing them as Japanese (3) use the words correctly in context -- which might mean incorrectly in terms of standard usage. Hirahara, and most other writers for that matter, might take a cue from Lois-Ann Yamanaka (b1961), who shows natural language without glosses, and uses italics only to show dramatic emphasis. In Wild Meat and the Bully Burgers (1996), there are several scenes involving tension between Lovely, the protagonist, and her English teacher. In one scene, Lovely makes a nice distinction between "pretend-talk" and what I am calling natural speech (1997 Harvest edition, pages 12-13).

Later Lovely makes this observation (pages 28-29).

In Father of the Four Passages (2001), Yamanaka includes this interesting passage in a letter from a father to his daughter (page 9).

A reader does not have to know the meaning of every word in a character's dialect or idiolect, or even entire lines spoken in an unfamiliar language, if the story is well crafted as a narrative of a human experience. Readers will know the meaning of the dramatic melody because they are human. All a good writer ever has to do is simply let the words rip -- and trust the reader to summon up their meanings. Spanish and EnglishHirahara did not treat Spanish with the contempt she treated Japanese. In at least two scenes (pages 24-25, 227-228), she interlaced Spanish into the English without glosses. She did not just let the Spanish rip, though, but degraded it with italics. Racial ambianceUnlike her linguistic misadventures, Hirahara's portraits of racial consciousness are credible. The characters she creates in her fiction reflect the true nature of race relations, red in tooth and claw as it were. The back cover describes Mas Arai as "just another Japanese American gardener" -- and the setting as "war-torn Japan to the rich tidewaters of L.A.'s multicultural landscape". Hirahara, to her credit, rarely resorts to such labels and language in her story.

Mas and most of his friends are usually described as "Japanese". The fact that they are Americans is inconsequential in a world in which they and most people they encounter think of themselves and others in racial terms. Accordingly, most others are "hakujin" -- which may be the frequently italicized word after "-san" and possibly "orai" (old port lingo, now standard Japanese). "inu" (dog, spy) also gets lots of play. The opposition of "Japanese" and "hakujin" precisely reflects the highly racialist and racist world in which Americans of Japanese descent live and survive -- by the seat of their own racialist and racist pants. Like most labels consisting of a racial, ethnic, national, religious, or other epithet qualifying "American" -- the first word to be dropped in ordinary social intercourse is "American". Nisei

The narration talks about Mas's friend Tug Yamada (pages 56-57).

Note, however, that Hirahara overgeneralizes -- not only here, but elsewhere -- much of what she writes about nisei and kibei. The in-line definition of "nisei" shows contempt for the reader's intelligence. The characterization of kibei -- though revealing Mas's doubts about his own Americanness -- clouds understanding of who kibei were as a subcategory of nisei. SanseiHirahara introduces "sansei" the same way, with equally intrusive historical commentary (page 148).

KibeiThough Mas and a couple of his friends are categorically kibei, Hirahara does a very poor job describing their situation in Japan. In one scene the narrator states that "There were plenty of other Kibei, American-born, at Koryo High School" (page 167), by way of setting up a scene in which Mas, during the war, at age fifteen, "went by the family registry office to see if he could join the navy like his two older brothers."

Hirahara has not told us that Mas is speaking perfect English, like the clerk, because in fact they are speaking Japanese, perfect or not. But such a conversation would be impossible in Japanese, then or now. There are several fundamental problems here.

The danger of using fiction as a "vehicle to explore social issues and cultural themes" is that, unless the author is very conscientious and thorough in doing research and checking facts, parts of the story presented as truth will end up as made-up and as false as the rest. Akemi surprises Mas by suddenly speaking "perfect" and "precise, clipped" English "as if she had never left Los Angeles" to a sansei attorney (page 186, 187). The attorney later cluches Akemi's shoulder and says, "It'll be all right, Obasan. Gam-BA-re" in what the narrator describes as "broken Japanese" with "terrible pronunciation" (page 216). HakujinMexicans, Latinos, blacks, Chinese, Vietnamese, and East Indians people Mas's world. There's an "Asian" with "dark skin" who Mas thinks is "Filipino" (page 159). There are kids whose skin she describes as "ranging in color from toffee to black-blue" and "smooth and unblemished, like perfect plumbs" (page 223). And there is "a dark boy who looked like a Hawaiian" (page 282). Though "Japanese" dominate the world of Summer of the Big Bachi, their world is dominated by hakujin, who leap off the pages in italics. The word "hakujin" is not glossed, though. The appearances and behaviors of hakujin are merely described.

KurochansHirahara puts "kurochans" -- which means "nigger" but goes unglossed -- into Stinky Yoshimoto's mouth (page 52). "Mas ignored Stinky -- he wasn't worth wasting time on," the narrator says. This might reflect Stinky's character. Or possibly Hirahara just wanted to use this word. JapIn a reminisence about his return to America, Mas tells Yuki, Akemi's grandson, this (page 208).

This is the only use of "Jap" in the story. One gets the impression that it was on Hirahara's list of words to use at least once. GaijinHirahara puts "gaijin" into the mouths of "MPs" -- her term for Japanese military police -- who taunt Akemi apparently because she is from the United States (page 218).

Race dominates nationalityIn one scene Hirahara describes the Evergreen Cemetery in Los Angeles (page 249).

Most readers would know that the nisei veterans were "dead" without Hirahara telling them. Some, though, might not fully understand that they were not Japanese but Americans. Hirahara, though, is very good at racializing the world through Mas's eyes if not her own. In Summer of the Big Bachi, she very skilfully portrays a world "divided by race: Japanese, hakujin, and the others" (page 271). "Underbelly of Japan"In the middle of the book comes what appears to be an aside on minorities in Japan. Keiko, who runs the ramen shop, is talking about her family, which own's a ramen house in Yokohama (page 146).

Gun in the drawerWhen you are told that there is a gun the drawer, you expect it to be used. Are Koreans going to appear in the story? Or will one of the characters turn out to be a Korean? Or is Summer of the Big Bachi not just a vehicle for lessons about what Hirahara considers her heritage as an American born to a kibei father and an issei mother -- but also, now, a tour of Japan -- or of what she calls its "underbelly"? One hundred pages later in the story it appears that someone is willing to pay much more for Akemi's land in Hiroshima than it is worth. Akemi's grandson, Yuki, describes the location of the land -- Ujina -- which Mas knew well. And as he pictures to himself "the makeshift shacks, the bald lightbulbs lighting up the shantytown at night" he wonders hy such a piece of land would be so valuable" (pages 243-244). Yuki has been writing for a magazine in Hiroshima, so Mas calls his editor and asks him to find out about the land. The editor says some people were hoping to build some new mansions on the Haneda land in Ujima. There were also some defense facturies in the area during World War II, he says (page 244). Mas remarks that there were some Koreans working and living there too (page 245). The editor agrees to "do some nosing around" and calls back an hour and a half alter (page 245).

Thirty pages later, toward the end of the story, the narrator finally suggests, through dialogue that sounds like a continuation of the "underbelly" sidebar, why Akemi's land, which "used to be next to this shantytown full of Koreans who ahd been forced to work in Hiroshima" might be worth a murder or two (pages 274-275). Narrative dishonestyHirahara has resorted to what I call "narrative dishonesty" in her bid to lay the foundation for the what she thinks is a clever idea. First, she has contrived an unconvincing reason to introduce the "underbelly" side bar.

The reason given for Haruo's ignorance about Chinese in Yokohama is totally unconvincing. Yokohama is on the other side of the world from Hiroshima. Though Mas may have been more streetwise when the two men were in Hiroshima, it is not clear how Mas himself came to learn about Yokohama's Chinatown -- or why Haruo would not by now have heard anything about it. Haruo Mukai may have led a sheltered existence in the past, but the blast at Hiroshima had to have changed his outlook on life. We are told at the outset of the novel that he "had a shock of white hair that usually covered the left side of his face -- and "underneath that hair [was a] keloid scar, puckered and webbed, from the eyebrow to the chin [and a] fake eye, which needed to be adjusted] (page 12). This same Haruo is described as living in a small apartment in the Crenshaw area of Los Angeles while seeing a counselor in Little Tokyo to rid him of his gambling habit (page 14). Mas doesn't like to go there, especially after the riots. Haruo chides him for being too nervous, reminding him that a Japanese eatery called Kiku's was protected by neighbors who put signs saying "Black-owned" on its barred windows (pages 14-15). Though it is clear that Haruo is now more at ease than Mas in "the underbelly of America" (to paraphrase Hirahara) -- suddenly, and inexplicably, he is the butt of Mas's claim that he is silly because, having been a mama's boy in Hiroshima, he knows nothing about the underbelly of Japan. Hirahara has plenty of cause to feature Mexican gardeners, black store owners, Koreans, Chinese, hakujin, and Japanese like Junko -- who is fifty and trying to look twenty-five and wants a green card -- for they are very much a part of the natural fauna in Mas's world. But there is no reason in her story, except as she has contrived one, for her to talk about Chinese and Koreans in Japan. Second, although the narrative usually reveals what is going on in Mas's mind about people, and what he is thinking, here his conversation with the magazine editor is only partly -- and of course very selectively -- revealed. Discovery of motivationThe story would have been must smarter if questions about motivation had been more carefully developed as soon as it became clear to Mas that someone was after Akemi's land. Developers seek land for many reasons and use many tactics to get land. Some developers have used strong-arm tactics, working through gangsters who have stakes in a real estate agency or construction company. It would have been more realistic to suspect more conventional motives behind the land dispute. Then, toward the end of the story, the plot line could have taken a twist as Mas discovers the Korean angle -- revealed through a less contrived and more credibly narrated human drama. The basic plot of Summer of the Big Bachi is sound enough. The plotting, though, is chotto, a little, chuto hanpa, half-baked. |