|

Frank Chin

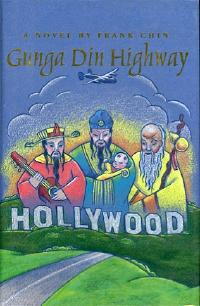

Gunga Din Highway

Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 1994

404 pages, hardcover

Both Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto have outlived Earl Derr Biggers (1884-1933) and John P. Marquand (1893-1960). If Mr. Moto has died except in re-issues of Mr. Moto stories, and early-morning re-runs of vintage films, Charlie Chan is still alive and well as Peter Ustinov in Charlie Chan and the Curse of the Dragon Queen (1981).

Charlie Chan has also been kept alive by attempts to kill him. He is already dead, according to Jessica Hagedorn's anthologies of Asian American literature, Charlie Chan is Dead (1993) and <. But the famous detective continues to haunt us in the critical writing and dramatic and fictional parodies of Frank Chin, the harshest and most convincing detractor of Charlie Chan lore.

In his novel Gunga Din Highway (1994), Chin features the Chinatown Black Tigers, a revolutionary group that pledges to "hunt down the last living white men to play Charlie Chan and try them before a People's Court" (page 220).

Ulysses Kwan, the protagonist, shares this sentiment but regards the Chinatown Black Tigers -- a parody of the Black Panthers of Oakland, where Chin grew up -- as a "yellow minstrel show" (page 219).

Ulysses says his actor father, Longman Kwan, "is sure he has a better chance than [Marlon] Brando at playing the lead in the next Charlie Chan movie. Brando's too expensive for a Charlie Chan movie." (page 219)

Longman Kwan had played Chan's Number Four Son before becoming "the Chinaman who dies" in one Hollywood epic after another. Yet he clings to his dream of being the first Chinese American actor to play Charlie Chan -- an aspiration Ulysses despises -- and which Frank Chin, writing in another voice, would call "a strategy for white acceptance" ("Interview", in Studs Terkel, Race (How Blacks and Whites Think and Feel About the American Obsession), New York: The New Press, 1992).

Gunga Din

"Gunga Din" (1892) is the title and hero of one of the more moving poems by India-born Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936). Gunga Din is a non-combatant water carrier, and a hero in the eyes of one of the soldiers he serves, the narrator, Thomas Atkins, who is fighting in a war that is not his.

"Gunga Din" begins like this --

You may talk o' gin an' beer

When you're quartered safe out 'ere,

An' you're sent to penny-fights an' Aldershot it;

But if it comes to slaughter

You will do your work on water,

An' you'll lick the bloomin' boots of 'im that's got it.

Now in Injia's sunny clime,

Where I used to spend my time

A-servin' of 'Er Majesty the Queen,

Of all them black-faced crew

The finest man I knew

Was our regimental bhisti, Gunga Din.

-- and ends like this.

Din! Din! Din!

You Lazarushian-leather Gunga Din!

Tho' I've belted you an' flayed you,

By the livin' Gawd that made you,

You're a better man than I am, Gunga Din!

Frank Chin, through Ulysses, puts the last stanza -- from "You Lazarushian-leather Gunga Din!" -- in the mouth of a black linguistic genius named Abdul who "speaks every civilized language of Europe, Asia, and North Africa fluently" including Cantonese. Abdul, drunk, recites Kipling in Cockney, from the roof of his car in the middle of the intersection of Telegraph and Haste in Berkeley, just south of the University of California campus. The next morning "he borrows a gun, loads it with dumdum shells, walks into the Bancroft Library on campus, and blows his girlfriend's brains onto the library table. Then he puts the gun to his temple and fires, but the dumdum shell is defective, and instead of expanding and exploding out of his head, the bullet whizzes around the inside of his skull and comes out his right eye." (Page 152)

Fu Manchu Plays Flamenco

Ulysses grew up with two friends, Benedict Han and Diego Chang, who also narrate parts of the novel. Using letters from Ulysses and one of Sax Rohmer's novels, Ben writes a play he calls Fu Manchu Plays Flamenco, and in one his turns at narration he relates this exchange with Diego about the play's authorship (page 217).

I phoned Diego to ask what he thought about me calling Ulysses' writing my own. "He has to do it, man," Diego said, "Your MFA is in danger and only he can rescue you. And anyway, as my Minister of Education, he says he's given up art for the people. So go ahead, do it, buddy!"

Ulysses liked the play. He didn't care what kind of scam I was trying to run. "One for all and all for one," he said. None of us had any thought that Fu Manchu Plays Flamenco would play in New York and give me my Warholian fifteen minutes of fame.

Chin is alluding both to his own fame in the early 1970s when his script for The Chickencoop Chinaman won a prize and was produced in New York -- and to the generation of writers who are graduates of Master of Fine Art schools, where they learn to barter their souls for marketable ideology.

Kool-Aid, Bisquick, and Crisco

Diego remarks, a few pages later, that Fu Manchu Plays Flamenco was being produced in New York. Ben has cast Ulysses as Fu Manchu, but since Diego himself was the model for the flamenco-playing Fu Manchu, he also goes to New York, where he is needed to play the guitar (page 247).

Chin lets Diego reveal the plot of the play by way of describing a conflict between Ben and Ulysses over how to go about changing the script (page 258).

In the play, Fu Manchu tells the white captive to give up the secret to Kool-Aid or he will let his beautiful nympho daughter give him the dreaded torture of a thousand excruciating fucks and exotic sucks. But the white man defends the secret to Kool-Aid, and Fu's luscious daughter wheels the captive off to her silk-sheeted torture chamber. When the director sees Ulysses offstage watching, still in character, he tries putting Fu Manchu back onstage, reciting classical Japanese haiku of Issa and Basho, breathlessly watching his daughter torture the white man by seduction. Then Ulysses gets the idea to have Fu play the guitar in rhythm to his daughter's hips while badmouthing the white captive's sexual organs, skills, and style in Spanish, English and three dialects of Chinese.

Ben asks Ulysses to tell his ideas to him, during a break or at home, before spilling them out to the director in front of everybody. Ulysses didn't think it mattered. I didn't think it mattered. One for all, all for one.

So who knows and who cares whose idea it is for Fu Manchu to end his flamenco in the torture chamber by ripping open his robe and showing his body in a bra, panties, garter belt, and black net stockings, licking his lips as he makes a move on the white man, while Fu's daughter straps on an eight-inch dildo? The captive American screams the secret formula, not only for Kool-Aid but for Bisquick and Crisco, too.

Thus does Chin kill two of his favorite birds with one stone: (1) his thesis that a lot of Chinese American writers pander to the white market with Chinese culture as "fake" as Chinatown flamenco, and (2) his thesis that Fu Manchu makes all Chinese men seem like sissies in the eyes of Chinese women, who lust after beefy white men who exotify and eroticize them.

Pandora Toy

Ben has fallen in love with Pandora Toy, who has written a bestseller called A Neurotic Exotic Erotic Orientoxic, in which she confesses all (page 251).

I wish I were just a woman who loved sex. Instead, I am a Chinese woman who loves sex. There are no men, or attractive, precocious, muscular boys in Chinatown. There are only Chinese who tell little girls the story of the beautiful princess whose father, the king, flayed her foreign sweetheart to the death, held a banquet to announce her wedding, and gave her hand in marriage to the prince who belched the loudest. . . . I cannot seriously believe Chinese women have ever found an evening of [Peking] opera with all that belching sexy. . . . When I think of such a tradition, all I can do is sign. With all the erotic exotic orientoxic women like me, past and present, I sigh.

But I have to be honest. It is nice to be exotic. Exoticism makes any man I want for a quickie or for a night mine, all mine. Not being the naturally humdrum everyday plain universal Caucasian woman makes me stand out in a crowd. And I was born to stand out. At times I worry about what effect my exotic birth and sexual temperament is having on the authenticity and honesty of my behavior. But how can I know, when I am truly and righteously as free as I can be, having been born a girl within the labyrinth of a sadly unmanly culture, a culture with a language that uses the same word for "slave" and "woman"?

This is vintage Chin, who has criticized a number of popular Chinese American writers for misrepresenting Chinese culture in America, and for emasculating Chinese American men, as much as Sax Rohmer and Earl Derr Diggers did through Fu Manchu and Charlie Chan.

Credibility of belching

Diego relates an argument Ben and Ulysses have over whether the sort of "Chinese culture" that Pandora Toy panders as a toy of while publishers is "credible" (pages 260-261).

"Credible?" Ulysses snarls. "Remember all that shit we had to learn in Chinese school? Did anybody belch and win a woman in any of those stories? Huh?"

"Ulysses, come on, don't be that way. You know you've heard that said about the Chinese."

You ever heard any Chinese say it's polite or sexy to belch at the dinner table?"

Yes, of course. Pandora Toy and her mother!"

You heard Pandora Toy's mother say it's polite to belch as loudly as you can at the dinner table to show your appreciation of the mean?"

She says, I mean her first-person narrator, says she heard it from her mother," Ben says. "Chinese enough for you?"

Hey, the first place that anybody, anywhere, anytime, in any language read such a thing was when Pearl Buck said the only good Chink is a Christian Chink, and that belching at the dinner table is good manners to the Chinese. Then the whites invented the Nobel Prize for literature and gave it to her. That showed us!"

It's fiction. It's first-person fiction. A character whose thought processes show the effects of the diaspora."

The Village Voice didn't say it was fiction. The publishers of the book don't say it's fiction. It's on The New York Times non-fiction best seller list. It is not presented as fiction, it's presented as autobiography."

"She explained that to me, man, listen. They would only publish her book as nonfiction. They didn't think it would sell as a novel. Fiction, nonfiction, that's marketing. Read her book. She creates a Chinese culture that is acceptable to whites by rewriting a little of this and a little of that, in order to show higher truths, inner meanings. As far as I'm concerned, she's doing exactly what we're doing with the play."

"What are we doing with the play?" Ulysses asks.

We are revealing the truth of the Chinese culture we reject and creating a Chinese-American culture that is more humane, more considerate of women, more . . ."

Aw, bullshit! Fu Manchu Plays Flamenco is creating a Chinese-American culture that kicks white racism in the balls with a shit-eating grin," Ulysses sneers.

Sucking off white fantasies

The argument between Ben and Ulysses heats up. Ulysses, like Chin, does not mince his words (pages 261-262).

The fact is that Chinese literature . . . has nothing to do with your fiancee's strange tales. The stories she says are Chinese aren't and never were. She's not rewriting Chinese anything, man. She's just doing a rewrite of Pearl Buck and Charlie Chan and Fu Manchu."

"Right, just like James Joyce at the end of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, man, she is forging the uncreated conscious of the Chinese in the smithy of her soul!"

"Are you saying substance doesn't matter, that she can suck off the white racist fantasy as long as she does it with style and makes money at the same time?" Ulysses shouts.

"That's just what I'm saying! If anyone deserves to profit from the white racist fantasy, we Chinese Americans do," Ben laughs.

"Excuse me, Gunga Din, but what you describe is sometimes called selling out," Ulysses says, looking ugly.

"Grow up, man!" Ben laughs. "The only way we can make it in America is to sell ourselves. No one wants to buy our folk tales. But they like buying exotic Oriental women and Oriental men who are either sinister brutes or simpletons. So why not sell it to them?"

Why not indeed. In this way every page of Gunga Din Highway gets better -- or worse, depending on one appreciates Chin's infamous sense of humor, and agrees that the Gunga Dins and Pandora Toys of the world are selling something out. (WW)

|