James Hadley Chase

Chinks, Chinamen, and dolls

By William Wetherall

First posted 10 January 2006

Last updated 23 August 2009

See also review of Yellow Peril: Collecting Xenophobia.

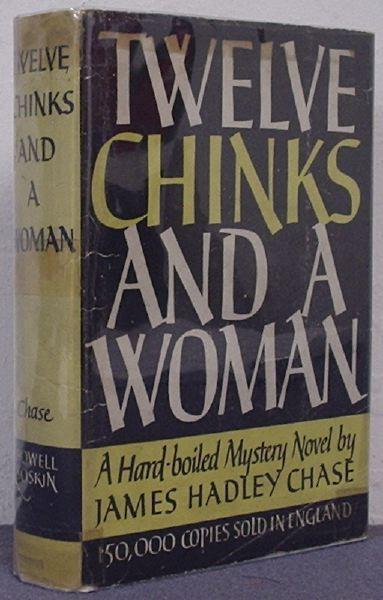

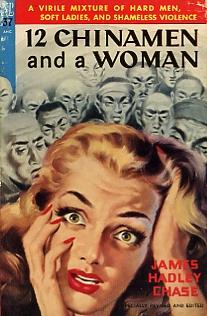

Twelve Chinks and a WomanJames Hadley Chase was a pseudonym of Rene Lodge Brabazon Raymond (1906-1985), who also wrote as Raymond Marshall, James L. Docherty, and Ambrose Grant. Raymond was born in London, and as James Hadley Chase was one of the most productive and popular mystery thriller writers of his day. Twelve Chinks and a Woman, first published in 1940, was Chase's third novel. It came out a year after No Orchids for Miss Blandish, his hugely successful debut work, also read in the United States as "The Villain and the Virgin". "Twelve Chinks" also came on the heels of The Dead Stay Dumb (1939), published as "Kiss My fist!" in some US editions. An Australian antiquarian book dealer describes a later printing of the first edition of "Twelve Chinks" as follows:

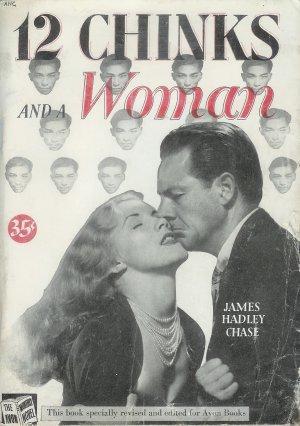

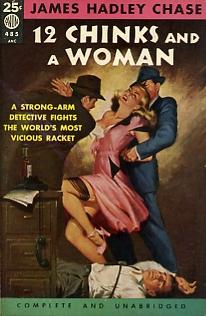

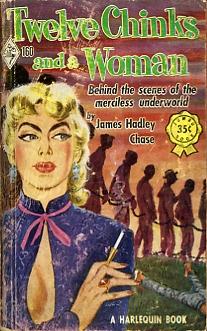

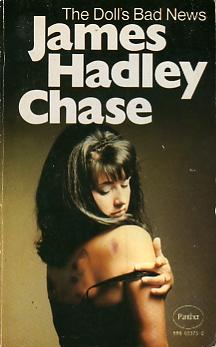

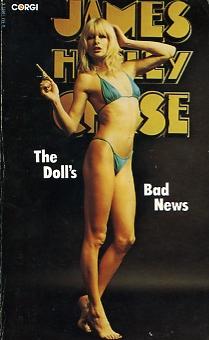

Publishing historyHere is a very rough outline of the publishing history of "Twelve Chinks". Not all of the information has been confirmed. 1. Twelve Chinks and a WomanFirst UK hardcover edition 1940 Jarrolds First US hardcover edition 1941 Howell, SoskinDigest and paperback editions Avon Monthly Novel (digest size, edition 7) Avon paperback (Complete and Unabridged) Canadian paperback 1952 Harlequin Books (Number 160) 2. Twelve Chinamen and a WomanDiversey paperback (Specially Revised and Edited) 3. The Doll's Bad NewsUK paperbacks 1970-1975 Panther Books (143 pages) Avon and Novel Library blurbsBoth the Avon and Novel Library editions have this blurb on the inside front cover.

The back blurb of the "Chinks" edition reads like this.

The Novel Library version differs only in two places: (1) NO ORCHIDS FOR MISS BLANDISH becomes THE VILLAIN AND THE VIRGIN, the alternative US title, and (2) CHINKS becomes CHINAMEN in the title. The storyThe hero of "No Orchids" -- a reporter turned private eye named Dave Fenner -- is also the hero of "Twelve Chinks", which is set in New York and Florida. In the very distant and barely seen background is a human smuggling operation that moves Chinese, a dozen at a time, from Cuba to Key West, then to other places, like New York. Fenner is a typical hard-boiled private eye with an attitude that walks the line between wiseguy and sainthood. As such, he represents every male reader's ego, labido, and superego -- one always pulling at the other. A frightened woman comes into Fenner's New York office and wants him to find her sister (page 7, Avon 485 edition).

Later Fenner finds a dead "Chinaman" in his secretary's office. The man's throat had been cut and he had been dead for a while. Fenner talks with his secretary, and later with police investigators, about the "Chink" aka "Chinaman" who has been dumped on his premises, more as a warning than to get him into trouble. The "Chinaman/Chink" -- and "Chinese" as the man is also called at times -- is just a body. He has no name. He is a victim, not a villain, at this stage in the story. He and the "twelve Chinamen" play practically no role in the story. In fact, he and his death remain very much a mystery until the wrap-up toward the end of the novel, when the woman's reference to "twelve chinamen" also becomes clear. The "Chinamen" are just people Carlos, a Cuban, smuggles into the United States from Cuba for a man named Thayler, who "pays Carlos so much a head, and sells the Chinks to sweat shops up the coast" (page 118). Fenner tells Glorie she's "not exactly an angel". She's been letting Thayler handle her the way he likes. He was married and she was married, and Fenner confronts her about her desire to get a divorce so she can marry him (page 118).

The doll's bad newsThe dead man's name, and his connection with Glorie, are not revealed until final pages of the story. Fenner has already pieced together most parts of the puzzle, but he still can't see the entire picture. Nightingale, who has been shot and is dying, tells Fenner all he knows about the dead "Chinaman" -- his name, and who killed him and why (page 144, some parts abbreviated)

Nothing in the story condemns Glorie for taking up with Chang because he is a Chinaman. Fenner tells her "a story about a nasty little girl and a Chinaman" -- which she doesn't want to hear (page 153).

Glorie, the "bewitching blonde", is guilty mostly of a wanting that drove her from man to man, and to a "variety" of men, while still married. It is her inability to control her insatiable hunger, not the fact that she happens to gratify it with Chang, that makes her "a nasty little girl". Glorie has lost the only man who had been able to give her whatever it was she wanted from him. The narrative is ambiguous as to how she herself actually felt about Chang as a person, as neither he nor their relationship is developed. However greedy and disloyal she has been, she is always shown to be emotionally upset that he has been killed. Glorie witnessed Chang's murder -- and describes it to Fenner in a manner than makes Chang somewhat of a hero (pages 153-154).

Fenner tells Gloria she's not very nice. He can't feel pity for her because she always thought of herself first. It would have been fine she would have had her revenge, at the risk of losing everything she had. But she didn't have the "guts" to give up Thayer in the process of getting back at Carlos. The story twists and turns a bit more before Fenner, in the final scene, frees himself of the bad news "doll" named Glorie (page 156).

Fenner leaves her with her husband, and the story ends. Justifications for title changesThe main justification for the change of title from "Chink" to "Chinaman" would be that the latter was actually the more common vulgar reference to "Chinese" at the time. I recall an incident that took place in late 1958 during an algebra exam in my senior year at high school. The teacher overheard a boy sitting beside me whisper a plea for an answer. He called him by name, told him stop talking, then said, "You're making Wetherall look like a Chinaman." Students who had started laughing when the teacher began scolding the boy fell dead silent. After class, the teacher apologized to both me and the girl, whose name was Lum. I am talking about Grass Valley, a small mining town in Northern California. The roots of a number of the older "native" families in the town went back to Chinese who had come to the area during the Gold Rush. Of course these were American families. More importantly, though, they were local. And so Lum had grown up with her classmates and was very much a part the class. I witnessed some name-calling from kids who didn't know them, but I can't remember anyone who knew them tolerating disparaging references to their ancestry. Hence the sudden silence in the class. The teacher, who had not lived in the are very long, had clearly stepped over a line he was not even aware of. I myself had recently moved into the area, but from San Francisco, where I had attended the 7th grade in a junior high school near Chinatown, where one-third of the students were Chinese Americans. In the mid-1950s, boys were still playing war, and someone had to be the enemy, and the enemies were Japs, Gooks, Commies, and Reds. "The Reds are coming!" was sort of like saying "The sky is falling!" The best argument against the "Chink" and "Chinamen" titles are that the story really has little to do with Chinese. These titles, and the cover blurbs and art that exploit them, are good examples of the sort of false advertising that characterizes the marketing of such fiction: the promise of lurid interracial sex is never delivered. Whereas the best literary argument for "The Doll's Bad News" is that it best expresses what the story is really about -- and in a voice that is even more faithful than "Chinks" or "Chinamen" to the stylistic conventions of the "romantic thriller" genre. |