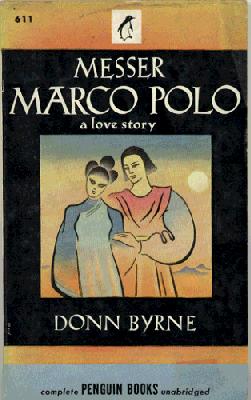

The Steamy East (1)Marco Polo et alBy Mark SchreiberMainichi Daily News Messer Marco Polo, by Donn Byrne, was first published in 1921. The cover is from the first Penguin Books edition of 1946. The Steamy East -- its mere mention conjures up scenes of adventure and romance: taipans and typhoons; jinrikishas and junks. Not to mention beautiful and exotic women; swashbuckling swordsmen and despotic warlords; the sweet-but-deadly smells of smoldering opium. Present-day Asia is no less exotic than the one of yesteryear. And although such amenities as air conditioning indoor plumbing have made the traveler's life more bearable from Calcutta to Kobe, the Steamy East is still no place for the timid. And so it is that for most of us, the safest route to Asia has long been through literature. It was poet Emily Dickinson who wrote the immortal lines "there is no frigate like a book." While agreeing wholeheartedly, this writer would change the word "frigate" to read "time machine." For it is books that give us the greatest opportunity to look back at the past centuries when Europeans -- traders, missionaries and adventurers alike -- began to set roots down in the East. Marco the MagnificentAlthough southern China had been accessible to seafaring Arab traders until the latter part of the 9th century, it took the combination of Venetian expansion eastward and Mongol expansion westward to produce the formula that linked Europe with the Far East. The individual best known as the pioneer in such endeavors, and certainly one of the world's all-time great travelers, was a 17-year-old Venetian named Marco Polo who went east in 1271. Polo is popularly credited as being the first European to travel overland in the Far East; actually though, young Marco followed in the footsteps of his father and uncle, who made an earlier journey in 1260. It was his astonishing book, know in English as The Travels, that assured Marco, and not Polo senior, the honored place in the annals of history. What is not widely known is that Polo's book was at least partly ghostwritten. As history records it, after 20 years of service to the Great Khan, Polo returned to Venice in 1292. While incarcerated as a prisoner of war by the Genoans in 1298-99, it is believed that he penned his book together with the help of a fellow cellmate, a romance writer named Rustichello. The stories of China, India, Burma and the Silk Road brought back by Polo must have seemed incredulous to Europeans of those times. Traveling to Hangchow, the magnificent former capital of China under the Southern Sung dynasty, Polo described it. thus:

Tradition has it that when the 70 year-old Marco lay on his deathbed, he was urged by his priest, relatives and friends alike to confess his countless lies, upon which, in the words of a contemporary biographer, the unrepentant old man "raised up, roundly damned them all, and declared, "I have not told the half of what I saw and did!"' More recently, American author Gary Jennings published "The Journeyer," an entertaining best seller intended as a sort of unexpurgated version of Marco's Travels, based on the implications of the above mentioned deathbed remark. Be that as it may, the Silk Road and other overland routes to Asia proved too difficult for large-scale trade, especially after the downfall of the Mogul empire. It was to take another two centuries before the next wave of Europeans, led by the Portuguese, were to set the stage for further expansion in the East. |

www.wetherall.org