Studies of Steamy East images

How people see themselves and others

Here you will find reviews mostly of books, but also of a few articles, that address how people see themselves and others, and/or examine the images of the regions and countires that figure in Steamy East fiction.

Commentary on "yellow peril" is ubiquitous in writing on images of Asia. Only general works with "yellow peril" in their title or subtitle will be reviewed here under Yellow Peril. Books or articles that focus on "yellow peril" in fiction, for example, will be listed under Fiction in the Media section.

The main Images page is fully viewable in this window. You can jump to any part by clicking on its link on the menu, or scroll or search for keywords (Ctrl F) within this window.

Clicking on any link to another page within Steamy East, or to another website, will replace this page on your browser.

| Mutual illusions |

|

Biologically all animals, including humans, are born with the capacity to develop ways of identifying friends and foes. Humans do this physically through the usual sensory devices, including smell and sound and shape and color. But humans also develop bodies of knowledge in the form of images that are passed on from generation to generation through spoken and written words. If one is intrigued by the the motion of the heavenly bodies, and comes up with the idea that they revolve around the earth, then these ideas remain truthful until there is cause to doubt them. It is the same with images that people have of themselves and others. Even habitually losing feuds or wars to inferior neighbors may not shake cherished beliefs in the supremacy of ones own family, tribe, or nation. That such illusions of superiority are almost always mutual is not ironic, because human nature could not be otherwise. Only when conflicts between rivals are replaced by conflicts which force the rivals to cooperate, do they begin to discover that many of the assumptions they had been making about each other are not correct. (WW) To be continued. |

| Occidentalism |

Ian Buruma This book is vintage Buruma. For several years my editor at the Far Eastern Economic Review, Buruma gets my vote for the most cogent and credible writer on the human condition in greater Asia and other parts of the world, of anyone writing today. The sheer breadth and depth of his commentary belies the labeling of him as just an Asianist, much less a Sinologist or Japanologist. Twenty-five essays are grouped in three parts. Part 1

Mishima Yukio: The Suicidal Dandy Part 2

Satyajit Ray: The Last Bengalil Renaissance Man Part 3

Ghosts of Pearl Harbor Many of these essays will shock readers who believe that "Asia" exists -- except as just another cauldron of humanity. (WW) |

James Carrier (editor) Almost as soon as "Orientalism" became a buzz word, some scholars began calling its counterpart "reverse Orientalism" -- an expression not used in this book. This simply meant that, if Occidentals "constructed" the Orient to serve their own purposes, Orientals constructed the Occident to serve their purposes. Life was simpler in those days, before anthropology became totally polluted by postmodernism, which feeds on obfuscation. Now even a rocket scientist would have trouble reaching the moon through the terminological haze. "orientalism" versus "Orientalism"In his Introduction, James Carrier, an anthropologist at Durham University who specializes in Melanesian society, defines "occidentalism" as meaning "stylized images of the West". He also differentiates "orientalism" from "Orientalism" (page 1). [Edward Said's Orientalism] is so influential that 'orientalism' has become a generic term for a particular, suspect type of anthropological thought. (In this collection, 'orientalism' marks the generic use of the term, 'Orientalism' being reserved for the specific manifestation Said describes.) As though they didn't have enough to do, readers are asked to differentiate between "Orient/alism" and "Occident/alism" on the one hand, and "orient/alism" and "occident/alism" on the other. Yet they must second guess the intent of such terms when capitalized at the beginning of a sentence, or in titles, simply because house style requires uppercase. Readers are also left wondering why, if there is an "orient" and an "occident", there are no "east" and "west" counterparts of "East" and "West" -- and why people are always "Westerners" and "Caucasians". No wonder the twain never meet in academia, where it is still fashionable to take seriously the notion that it is useful to dichotomize the world this way. ContentsThe convoluted prose that detracts from many of the articles is partly mitigated by their geographical spread. 1. Cargoism and Occidentalism 2. The Kabyle and the French: Occidentalism in Bourdieu's Theory of Practice 3. Maussian Occidentalism: Gift and Commodity Systems 4. Occidentalism as a Cottage Industry: Resenting the Autochthonous 'Other' in British and Irish Rural Studies 5. Imaging the Other in Japanese Advertising Campaigns 6. Duelling Currencies in East New Britain: The Construction of Shell Money as National Cultural Property 7. The Colonial, the Imperial, and the Creation of the 'European' in Southern Africa 8. Hellenism and Occidentalism: The permutations of Performance in Greek Bourgeois Identity 9. Occidentalism in the East: The Uses of the West in the Politics and Anthropology of South Asia Inside and outside "the West"Carrier broadly defines two kinds of occidentalisms, one internal, the other external. The former, "Occidentalism", exists in "the Western mind" (to paraphrase Carrier) in opposition to the "Orientalism" that exists in the same mind. The latter, which Carrier calls "occidentalism", exists "beyond the West" and appears "in studies of the ways that people outside the West imagine themselves . . . in contrast to their stylized image of the West" (page 6). This stylized image leads people "beyond the West" to take an "external view of themselves and their way of life [in order] to see their culture as a 'thing'" (ibid.). And this "occidentalized perception of themselves" (my wording) leads them to reformulate their indigenous social life accordingly. Loopy terminologyUp to this point, the rules of the terminology game are fairly clear if not simple. But things suddenly get very loopy. Here is, verbatim, an entire paragraph from the first chapter, which attempts to change the rules (Lamont Lindstrom, "Cargoism and Occidentalism", pages 35-36). Some terms3 Carrier (1992b: 198), taking note of power differentials within the world system of the past several centuries that influence the relative capacities of different peoples to define and describe one another, proposed the terms 'ethno-orientalism' and 'ethno-occidentalism'. These terms label discourses about the self, in the former case, and discourses about the West, in the latter, that orientals themselves have devised in parallel with our orientalism and occidentalism. For purposes of this chapter, I would like to ignore the slant of the historical playing field and use, instead, the term auto-orientalism to refer to self-discourse among orientals. In this scheme, thus, occidentalism is discourse among orientals about the West. What Carrier and others have called occidentalism, I will call auto-occidentalism -- the self-discourse of Westerners (and this term should replace my use of occidentalism, above). This terminology allows me several additional labels that are important for a reading of cargo cult tales. These include internal-orientalism (or, in this case, internal-Cargoism) (the location of the orient (here, cargo cultists) at home); auto-Cargoism (an adoption of Cargoist discourse by Melanesians to talk about themselves); sympathetic-Cargoism (Western constructions of the Melanesian that permit a measure of similarity between self and other); pseudo-occidentalism (or presumptions about what the oriental may be saying about the occident); and assimilative-Cargoism (the erasure of Boundaries so that stories of the oriental/Cargo other explicitly transform into stories of the self). The Cargoist archive is packed with internal-orientalist, sympathetic-orientalist, pseudo-occidentalist, and assimilative-orientalist elements that blur and even erase the boundary and the differences that separate us and them. Notes 3 Although my argument locates erasures of the boundaries between orient/occident, East/West, oriental/occidental, and orientalism/occidentalism, as I proceed I shall none the less have to maintain the essence of these categories as categories, as a manner of speaking, along with an essentialist 'cargo cult' and 'Cargoism' as well. Readers may supply their own quotation marks (See Carrier 1992b: 206-7). Things get betterSome of the reading gets better because it couldn't get worse. By the final chapter, though still very much in the throes of a postmodernist orgasm, thankfully there are no more nested brackets, and no more excuses for exceptionalizing one's one own rules in order to get upwind from the stench of one's own terminology (Jonathan Spencer, "Occidentalism in the East", pages 234-235). I start by looking at anthropological occidentalisms in South Asia, first in order to demonstrate the use of what I call the rhetoric of authenticity -- the use of the West as a rhetorical counter which guarantees the anthropologist's real understanding of the non-West; and secondly in order to justify this volume's choice of occidentalism as the master trope under which to subsume other dichotomies such as traditional/modern and rural/urban. I then examine some South Asian uses of occidentalism in the public sphere, where it serves above all as mnemonic for the cultural contradictions engendered by colonial domination. I do this by sketching the positions of three Sri Lankan figures, all nationalist writers from the middle and late colonial period. I also briefly discuss the version of Ghandi's 'affirmative Orientalism' recently presented by the Indian cultural critic Ashis Nandy. These examples allow me to reconstruct something of the political context of different occidentalisms, but in so doing I uncover an unexpected paradox: where anthropological occidentalism tends to efface the colonial encounter, indigenist occidentalism foregrounds it. In the face of this I offer one preliminary conclusion. Not only is essentialism an inevitable and not terribly remarkable feature of our world, as James Carrier points out in his Introduction. But, as the uses of occidentalism are at once various and complex, so simple-minded anti-essentialism is both politically and theoretically inadequate as a response. EssentializationIn Carrier's introduction, "to essentialize" means "to reduce the complex entities that are being compared to a set of core features that express the essence of each entity, but only as it stands in contrast to the other" (page 3). "In conventional anthropology," he continues, "the orientalisms that have attracted critical attention, thus, do not exist on their own. They are matched by anthropologists' occidentalisms, essentializing simplifications of the West." In Edward Said's view, according to Carrier, "The alien Orient . . . is essentialized, is reduced to a timeless essence that pervades, shapes, and defines the significance of the people and events that constitute it" (page 2). In a note to this statement, Carrier remarks that "To essentialize a group or region does not require that it be seen as static or simple. It can be construed as going through stages of development or evolution, as . . . occurs in nationalist essentialisms. Equally, it can be essentialized in terms of its complexity and continual change, as . . . is the case for Europe." (page 29, note 1). Essentially, this book testifies on the side of critics who hold that cultural anthropology has lost touch with reality. (WW) |

| Orientalism |

Rana Kabbani The author, billed as a poet and translator of modern Arabic poetry, was born in Damascus and received her BA, MA, and PhD in English literature from Georgetown University, the American University of Beirut, and Jesus College, Cambridge. The "Orient" in her book is that of the Arab and Islamic world as seen through Victorian and other European eyes. Powerful travellersKabbani is interested in travellers (pages 1-2) The traveller who sets out from a strong nation to seek out curiosities in lands less powerful than his own is to be found in many different civilisations.1 The Islamic world, for instance, from the seventh to the fourteenth centuries composed of military and political powers which held sway over an area that came to stretch from Spain to China, sent out travellers, either as emissaries or as explorers, to bring back knowledge that could be used to enrich the store of politically useful information. As the Arabs grew more powerful, the number of travel books in their literature increased accordingly.2 Thus begins a brief overview of "travellers" in other ages and places, all leading up to Kabbani's focus on 19-century European travellers in the Arab and Islamic world.(page 7). The nineteenth-century traveller was concerned with the scenery only as it served as backdrop for his progress. He was the journey's hero -- not merely its narrator -- and he spelled out his complacency, cherishing every opportunity to speak of the self. . . . After all, the mythic Self of the traveller contained the sum of what he transported -- his education, emotions, biases and beliefs, laced with a strong dose of racial conceit, as befitted a century of imperialist travellers. Richard BurtonNo one represented the period more than the British explorer and imperialist of all trades Richard Burton (1821-1890) (page 7). Richard Burton was one of the most prolific among these, a staunch empire man through all his wayward wanderings. And significantly, it is his narrative that did most to asseverate the fiction of an erotic East. The Orient for Burton was chiefly an illicit space and its women convenient chattels who offered sexual gratification denied in the Victorian home for its unseemliness. The articulation of sexism in his narrative went hand in hand with the articulation of racism, for women were a sub-group in patriarchal Victorian society just as other races were sub-groups within the colonial enterprise. Oriental women were thus doubly demeaned (as women, and as 'Orientals') whilst being curiously sublimated. They offered a prototype of the sexual in a repressive age, and were coveted as the permissible expression of a taboo topic. Visual seductionKabbani, squarely in the feminist school of orientalist studies, prefers telling good stories to discoursing in postmodernese. She presents some very interesting and compelling citations from the writings of travellers like Burton, Galland, Lane, Doughty, and Lawrence to support her contention that European fantasies about Egypt and the rest of the Orient were as sexual as they were racial, political, and religious. Kabbani's analysis of orientalist painting, which visually seduced European onlookers (page 73), is well illustrated with eight pages of clear glossy black-and-white reproductions of representative 19th-century art portraying Arabian men and women. (WW) |

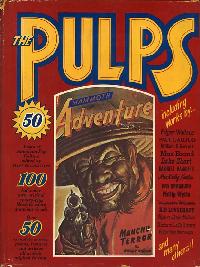

Sheng-mei Ma Sheng-mei Ma, a professor of American though and language at Michigan State University, received his PhD in comparative literature. He now teaches and writes on Asian American literature, minority discourse theory, Holocaust and other genocide studies, postcolonial literature and theory, Asian diaspora culture, and Asian literature and film. The title and subtitle of this book are actually meant to be read together, as Ma himself reiterates in his epilogue (page 161). I fully understand the consequences of my thesis -- the deathly embrace of Orientalism and Asian American identity -- and that it is likely to elicit strong reactions. But arguing in moderation is simply out of the question if one is to engage in a deconstructing of ethnic identity, as I point out in the Introduction. It is hoped that passion will not be mistaken for vitriol. Ethnicity in the arms of OrientalismThe following paragraphs are from the University of Minnesota Press web promotion of this book. The first paragraph also appears on the back cover. Asian American resistance to Orientalism -- the Western tradition dealing with the subject and subjugation of the East -- is usually assumed. And yet, as this provocative work demonstrates, in order to refute racist stereotypes they must first be evoked, and in the process the two often become entangled. Sheng-mei Ma shows how the distinguished careers of post-1960s Asian American writers such as Maxine Hong Kingston, Amy Tan, Frank Chin, and David Henry Hwang reveal that while Asian American identity is constructed in reaction to Orientalism, the two cultural forces are not necessarily at odds. The vigor with which these Asian Americans revolt against Orientalism in fact tacitly acknowledges the family lineage of the two. To identify the multitude of historical forms appropriated by the deathly embrace of Orientalism and Asian American ethnicity, Ma highlights four types of cultural encounters, embodied in four metaphors of physical states: the "clutch of rape" in imperialist adventure narratives of the 1930s and 1940s, as seen in comic strips of Flash Gordon and Terry and the Pirates and in the Disney film Swiss Family Robinson; the "clash of arms" or martial metaphors in the 1970s and beyond, embodied in Bruce Lee, Kingston's The Woman Warrior, and the video game Mortal Kombat; U.S. multicultural "flaunting" of ethnicity in the work of Amy Tan and in Disney's Mulan; and global postcolonial "masquerading" of ethnicity in the Anglo-Japanese novelist Kazuo Ishiguro. As Ma writes in his introduction (page xxii-xxiii): My approach as a whole is interdisciplinary, encompassing Asian American, American, Asian, and postcolonial studies; it is multigeneric, drawing from fictions, essays, children's books, films, comics, video games, and court documents; it springs from the field of cultural studies where a social phenomenon is anatomized in all its complexities, regardless of the barriers between "high" and "popular" culture, adult and children's culture. His commentary is augmented by seventeen consecutive pages of comic strips and other caricatures shown in black-and-white, and by five other full-page and four smaller black-and-white illustrations. Kazuo IshiguroI was particularly attracted to Ma's eighth and last chapter, "Kazuo Ishiguro's Persistent Dream for Postethnicity: Performance in Whiteface" (pages 147-160). Ishiguro is not an Asian American. He is British by way of migrating to the United Kingdom with his parents when a boy, and later naturalizing. Ma, of course, knows this. Why, then, wrap his thesis that "Asian American" identity has embraced "orientalism" with a look at a British writer he claims to be of "Anglo-Japanese" ethnicity? Ma has argued that "Asian Americans" will never be "Americans" because they themselves are embracing "ethnicity" rather than "postethnicity" as a way to defend themselves against orientalism. Ishiguro, Ma correctly claims, broke into writing on the strength of two "Japanese" novels -- A Pale View of Hills (1982) and An Artist of the Floating World (1986) -- contrived to go along with his Japanese name at a time when "ethnic" fiction was very marketable. This is precisely what "Asian American" writers continue to do -- whether one is a Maxine Hong Kingston (who Frank Chin calls "fake") or a Frank Chin (who thinks himself "authentic"). Ma views Remains of the Day (1989) and The Unconsoled (1995) as efforts on Ishiguro's part to escape the "ethnicity" imposed on him by his birth and upbringing and name. But Ma believes such efforts transcend his "Anglo-Japanese" self are merely a "Subversive Whiteface Reacting against Orientalism" and a "Reactionary Whiteface Subsuming Differences" -- as Ma states in the chapter's only two subtitles. "ethnic community" as racialist tyrannyThis is how Ma summarizes what he considers Ishiguro's failure achieve a white orbit around the pull of his ethnicity -- my expression for what Ma would call "passing" (pages 154-155). [N]either Remains nor The Unconsoled is truly postethnic. . . . Ishiguro's shift to English characters and postethnicity may suggest problematics much more troubling than a minority's reaction against identity politics by pigeonholing him as nothing but an Anglo-Japanese. Ethnic writers can conceivably imagine ways to become more, not less, ethnic. Why does ethnicity have to make way for postethnicity, an illegitimate heir that is probably one's own, yet alarmingly white? Why should the ethnic community accept one writer's flirtations with postethnicity, perhaps a code word for "whiteness"? Ma accuses Ishiguro of not writing hyphenated "Asian diaspora literature" (page 156). Ishiguro has so far masqueraded as Japanese (Ono), Anglo-Japanese (Etsuko), English (Stevens and Ryder), and vaguely Central European (the townspeople in The Unconsoled) characters in Japan, England, and an unidentified part of the Continent. The novelist inhabiting that hyphen has emerged in many roles, but rarely as an Asian minority living in the West, or, to put in unabashedly essentialist terms, in a subject position similar to his own. Ma finally tailspins into the sea of racialism (page 157). Ishiguro's dream of postethnicity turns out to be a veiling and an intensification of his minority complex. Freedom of choiceWhat, I would ask, is freedom for a writer -- if not to be able to choose what and who to write about? Ishiguro only began to write truly well and authentically when he realized he was British and not Japanese. Ishiguro, for his part, has diplomatically reminded every racialist interviewer who has found it amazing that a "Japanese" should be able to write a work of English fiction like Remains of the Day -- that he is British. Ma says that Remains of the Day "appears almost Conradian in its being more English than the English" (page 149). Ma himself cannot accept that Ishiguro might very well be English. He insists on treating Ishiguro like a piece of fruit: If doesn't look an apple, he shouldn't be trying to taste like one. It is people like Ma who, in judging Ishiguro by his birth and name, create the racialist climate in which not a few writers feel the pressure to "perform" an "ethnicity" that is not really theirs. When We Were OrphansIf Ma's The Deathly Embrace had been published one year later, he would have been able to read Ishiguro's When We Were Orphans (2000). The novel, set mostly in Shanghai, is about a famous London detective who returns to Shanghai, where he was born, only to find himself caught up in the Sino-Japanese War and his own memories. Why should anyone read any novel, except as an interesting (or not so interesting) story? Why should browsers pick up a novel by someone named "Kazuo Ishiguro" -- and return it to the shelf, disappointed because it lacks "Anglo-Japanese ethnicity"? Ma is also the author of Immigrant Subjectivities in Asian American and Asian Diaspora Literatures, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998. In this work, too, he contends that "Asian Americans" who attempt to empower themselves by practicing an "ethnicity" that defines itself in opposition to orientalism are never able to liberate themselves from is power. It seems to me that Ishiguro is far more liberated than the likes of any North American or British writer today who happens to be, by sheer accident, of racially "Asian" descent. (WW) For more examples of the sort of racialism that hounds Ishiguro as an "Anglo-Japanese" writer, see my Yosha Research article on Kazuo Ishiguro. |

Edward W. Said See also Orientalismism. Orientalism was published in the deconstructionist soil of Third World Studies, which had spread on campuses throughout the United States in the 1970s, after the radicalization of academia that had started flared during the 1960s. The purpose of introducing it here is to qualify its usefulness as an approach to Steamy East fiction. Two points need to be made: (1) Said's "Orient" does not extend east of the "Middle East", hence don't expect to find very much about China or Japan, and not a lot more about India; and (2) his assumptions about the human condition are much too political and ideological to facilitate a truly dynamic (both critical and sympathetic) understanding of Steamy East fiction. |

Edward W. Said [Forthcoming] |

Denis Sinor (Editor) Forthcoming. |

John M. Steadman Forthcoming. |

| Fears of domination |

|

Though "yellow peril" plots can be found in some Steamy East fiction, the fear some white people have at times expressed about being someday dominated by yellow people is not, in fact, a very likely theme. If anything, Steamy East fiction is anti-yellow peril in that most writers are apprehensive about evil, not race. It just so happens that, if someone writes a thriller from the perspective the United States and an American good guy, about a fictional enemy in China, say, the good guy is likely to be white, and the bad guy is likely to be yellow. But the bad guy is typically bad because he is evil, not because he is yellow. He is a despot or psychopath or communist or some combination, who has fanatical, personal, or ideological reasons to want to set off a nuclear bomb in the middle of Manhattan, whatever. But the same sense of "peril" can be found in most fiction that draws a line between friend and foe. The foe is rarely an entire nation or race or religion or whatever, but an evil leader or clan or government or the like. So "peril" exists whenever there are chronic or acute fears of domination or destruction by an individual or collective embodiment of evil, as we shall see in the varieties of peril found in Steamy East and related fiction. Racialized enemiesFear usually stems from real or imagined threats of domination by another people by any means -- from religious, ideological, cultural, economic, or demographic influence, intrusion, or invasion -- or through direct military invasion, conquest, and occupation. The fear is easily racialized as friction and other forms of conflict between two states increase the potential for war. And once war comes, neighbors of the same nationality can suddenly become racialized enemies -- as happened in the case of westcoat Americans of Japanese ancestry. The internment of Japanese Americans was not motivated by "yellow peril" so much as by war instilled fears of the "Jap enemy". Chinese immigrants and their American descendants, once racialized as threats to white domination in parts of California, had to be differentiated from Japanese immigrants and their American descendants, since China was an ally against Japan. Since the Japanese enemy was racialized, however, the perception of the "Jap enemy" was expanded to include Americans who just happened to be "Japs". Of course, such racism did not just pop out of thin air. It exploded out of a fertile soil of racialism that included "yellow peril" sentiments. Pearl Harbor simply reduced the civil barriers that had, until then, kept most racialist paranoia in check. White, Yamato, and red perilsStill popular in Japan today is the argument that Japan's intentions in China and the rest of Asia and the Pacific were partly motivated by a desire to drive the "white peril" out of Greater East Asia if not all of the Eurasian hemisphere including the west Pacific. This argument cannot be simply dismissed as Yamatoist conceipt. The great irony of Japan's adventures in Asia and the Pacific is that Yamato supremicism replaced the white peril with the Yamato peril. The Yamato peril swept China and steeled Chinese resistance to Japan's efforts to totally occupy and control the country. Chinese nationalists and communists called a truce to their civil war to drive out the common Japanese enemy. China's Yamato peril informed American, British, Canadian, and Dutch insistance that Japan withdraw from China. Japan, though, insisted it had a right to involve itself as it had in China's internal affairs. Pearl Harbor merely brought China's Yamato peril closer to home in the United States. And this peril, more than a "yellow peril", led to the injustices committed by westcoast states and the federal government against citizens of Japanese ancestry. The Yamato peril ended with Japan's defeat. But it was immediately replaced by the "red peril" in China as Chinese nationalists and communists resumed their civil war on a massive scale. Then came the Korean war, again involving Korean communist and nationalist forces, the communists backed by the USSR and PRC, and the nationalists by the US and its UN allies. The Vietnam War began when Japan left Vietnamese it has "liberated" from French colonialism to resist the return of the "white peril" in the country. Because that resistance was "red", the United States backed the southern "nationalists" who opposed the "red peril" in the north. Present-day perilsToday the worlds major perils are "materialism" and "corporatization" and "McDonaldization" and "Americanization" and "regionalization" and even "globalization". Many states also contend with "cultural imperialism" -- France its fear of English, Korea its fear of Japanese popular culture, China its fear of the Internet -- almost everyone's fear of Hollywood. NationalismNationalism infolves a lot of chest beating and flag waving and other expressions of extreme pride in nation, or the spread of a nation through colonialization whether by conquest or other means. Typically it is driven by racial or cultural supremacism, and by religious and other forms of ideological fanaticism. SupremacismSupremacism is at the heart of nationalism. Not all nationalists are ultrasupremacists, but most nationalists inevitable believe in the relative supremacy of their nation. A nation is usually regarded as superior for reasons of "race" (nature) and "culture" (nurture) -- "race" being the collective natural or biological traits of nationals, and "culture" being their collective way of life reflecting the superior values they acquired from having been nurtured in a superior society. ReligionStories that feature conflict resulting from religious or friction will be treated here. Most such fiction reveals the "Christian peril" -- the conspiracy between Christianity and Euroamerican imperialism to bring Christ and industrial civilization to Asia. Some stories deal with perceptions of the "Jewish peril" while others concern the "Islamic peril". IdeologySome states and private organizations have forced communisim, capitalism, democracy, and other economic and political ideologies upon countries or peoples they wish to change and control. Stories touching upon such ideological perils will be covered here. CultureStories which feature "culture shock" or "cultural misunderstanding" or "cultural imperialism" will be covered here. "Culture" is included here only because "cultural determinism" has become very fashionable. Many people have fallen into the habit of wanting to explain nations and even individuals in terms of a shared "culture" that governs collective and personal behavior. They are taught to say "my" and "our" culture and "your" and "their" culture -- and "nationalism" and "culture" are sometimes seen as two faces of the same "ethnic nation" or "race" of people. Many writers of Steamy East and related fiction motivate their characters as though were cultural cyborgs. A typical Steamy East novel is full of anthropological and sociological asides about the Asian countries and peoples featured in the story. Asian characters are apt to be portrayed not as personalities, but as culturally programmed robots. The abuse of "culture""Culture" has come to be one of the most abused words in the world. Its fashionability owes a lot to the impulse to explain people in terms of "their culture". In the United States today, thanks to the spread of multiculturalism, "culture" has become a code word for "ethnicity" and even "race". However, "culture" is almost always a thought-terminator when used to explain human behavior. It is blamed for all kinds of things it cannot possibly account for -- such as an individual's "culture shock" (personal inability to accommodate and adjust to an unfamiliar situation) or "cultural misunderstanding" (personal ignorance). The idea that there is "communication between two cultures" or "intercultural communication" is an even greater semantic travesty -- since cultures don't exist in forms that permit them to "communicate" in any sense of the word. Only individuals can communicate or fail to communicate. And no individual, or accoundable group of individuals, can mediate "a culture": they can only mediate those molecules of the vast, rare, and ill-defined cultural air they inhale in the course of their life. "Cultural imperialism" is arguably more credible as a metaphor of domination, since states and nationalist organizations are known to "bombard" and otherwise "invade" other states with information through radio, televison, films, books, and other media. DominationOne country can dominate another in many ways. Military conquest does not itself result in domination. In fact, some vanquished peoples have been able to co-opt the victors, who end up assimilating into the conquered population. Military dominationMilitary invasion and occupation is the greatest fear of every nation with a history of wars with neighboring countries. The age of intercontinental ballistic missiles, and Star Wars style attack satellites, has spawned fears of annihilation by frist-striking enemies on the other side of the globe. Science fiction commonly features alien invasions of earth, and wars between civilizations in differently parts of the universe. Demographic dominationNations are known to fear being over run by foreigners through gradual or mass immigration. Mass migrations can be triggered by wars or natural disasters that set huge numbers of refugees in motion toward a new homeland. Economic dominationHere we will look at stories that feature trade wars, sabotage of financial institutions, industrial espionage, and other such conflicts of an economic rather than ideological or military nature. Industrial espionage related to military domination will be under military. TerrorismStories featuring threats or acts of terrorism by any means will be covered here. Stories with plots involving nuclear or biological terrorism will under these headings. Weather terrorismNot yet in fiction but probably not long in coming -- now on only the wackier fringes of the Internet -- is "weather terrorism". Since 1990, according to one meteorologist, teams of yakuza and Aum Shinrikyo assumed weather engineering operations over North America from FSB/KGB. Since Aum Shinrikyo bad guys are in prison, the operations are being continued by the yakuza, who are said to be leasing giant scalar interferometers from Russia. Apparently these "rouge Japanese teams" are under direct FSB/KGB supervision. Biological terrorismMost stories involving biological terrorism are about threats or attempts to expose a city to a deadly microorganism, to force a government to capitulate to some evil man's demands. Nuclear terrorismNuclear terrorism typically involves threats to annihilate a city, possibly the capital of a country, if the government doesn't submit to the terrorits' demands. Japanese bad guys who resort to "nuclear blackmail" are often motivated by a desire to avenge Hiroshima and Nagasaki. |

| White peril |

Sidney L. Gulick Ramble House reprint edition Ramble House's blurb reads like this. At last we have a studied, rational view of the mis-interpreted motives of the Japanese rulers of the early 20th century. The author, Sidney L. Gulick, who must have been one of the very earliest members of Mothers Against Drunk Drivers (1905!), shows us in 118 detailed pages that Japan has never harbored any ill will towards any other nation and that there is no chance of this noble shogunate ever threatening any other country, much less attacking by surprise. Indeed, as is evidenced by the horrific visage on the cover of this brand new reprint, it is the despicable white race that bears watching. This 1905 book is an essential addition to any contrarian's library. Gulick's own "Preface" is more serious. On the 8th of February, 1904, Japan crossed swords with a European people. And from the destruction of the Variag on that day until the fall of Port Arthur on the 1st of January, 1905, nothing but failure has been Russia's fate, nothing but success Japan's fortune. For the first time in history has an Asiatic people successfully faced a white foe. The Russo-Japanese war marks an era, therefore, in the history of the Far East, and of the world, for now begins a readjustment of the balance of power among the nations, a readjustment which promises o halt the territorial expansion of white races and to check their racial pride. To appreciate the significance of this war as one act in the tragedy of the white peril we must understand Japan. How has she attained the power, material and temperamental, which is enabling her to face the white man and to conquer him? This question we study in our earlier chapters. In those that follow we study the significance of the war, and the problems of the Far East in their world-setting. We are not concerned with dates and battles, with armies and heroes. Rather shall we consider movements and tendencies, national ambitions and international relations. Emphasis is laid on the peril to the Far East of the white man's ambitions and methods. Justice to white races, however, demands recognition also of the blessings they confer upon those lands. In a real sense the white peril is becoming the white blessing of the Orient. Yet the aim of the present work in these pages precludes adequate emphasis of this point. Certain graceful writers, masters of imaginative style, have described Japan as ideal in every direction, a view widely popularized to-day by Japan's brilliant military record. But of course no thoughtful man will be misled, for national as well as individual perfection is impossible. Highly admiring Japan as I do, absence of criticism in the following pages does not signify acceptance of the popular unbalanced admiration. The decline of white dominanceGulick was not the only writer to view the outcome of the Russo-Japanese War as a watershed of race relations in Asia and even the world at large. Though Gulick had dedicated his life to the spread of Christianity, he appears to have acknowledged, to some extent, "the failure of Christianity to conquer the evils of Christendom" (page 55). Gulick seems to have realized that, whatever "blessings" western civilization might confer on some non-western societies, it could not fulfill its humanitarian promise so long as it was mediated by Christians who saw nothing wrong with white supremicism. In my words, rather his, the Church was incapable of abluting its own sins because, institutionally, it had swallowed the apple of racist imperial ambition, worms and all. The Great War of 1914-1918 also suggested that something was lacking in western civilization. In Der Untergang des Abendlandes [The twilight of the eveninglands], translated as The Decline of the West, the German philosopher-historian Oswald Spengler (1880-1936) espoused a cyclical theory of the rise and decline of civilizations and argued that Europe may have reached its peak. Spengler began the two-volume work, first published in 1918 and revised in 1922, before the war, so its scope goes far beyond Germany's defeat. Most observers of Japan, though, did not share Gulick's optimism that Japan was no threat to others. Koreans at the time had good reason to think of Japan as a peril, since both the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 had begun in Korea. And Japan annexed the Korea in 1910. By the early 1930s, the "Japanese peril" had spread in earnest to the Chinese continent, already having reached Taiwan in 1895. And the rest is history. Well, not quite. The history of "Second Sino-Japanese War" or "The Greater East Asian War" or "The Fifteen-year War" of 1931-1945 is still being written. So, too, is the "Pacific War" of 1941-1945. That Japan's military actions in Asia during the 1930s and 1940s were partly based on intentions to liberate Asia and the Pacific of Euro-American colonialism cannot be denited. The operational word is "partly". Partly, not entirely, since Japan clearly had its own imperialist designs on the region. But "partly" is enough to require that the "white peril" in Asia be taken into account in any revision of regional history. By William Wetherall |

Sidney L. Gulick, D.D. The "D.D." means "doctor of divinity" not "doctor of dentistry" -- but either way, it was like pulling teeth for Gulick to advocate an end to racism against Asian immigrants, as he did at a time when US immigration and naturalization laws prevented them from becoming US citizens on account of their "national origins" -- a code for "race" as it still is today. Raceless citizenshipIn Chapter IX -- Criticisms Criticized -- Gulick presents one of the most cogent, for its time, arguments for ending racism in US immigration and naturalization laws (pages 124-126) Let it be clearly understood, then, that the proposals of this volume have nothing to do with free Asiatic immigration. What we do urge will all possible emphasis is that those whom we do admit, and sho are to stay here permanently, whatever their race may be, should be urged and helped to learn our language and our ways and to enter thus into wholesome relations with our government and our people. [Emphasis in original] [abbreviated] American-born children are citizens, whatever their race. The withholding of citizenship from Asiatic parents will not have the slightest effect upon the chance that their American-born boys and girls may intermarry with girls and boys of long American ancestry, if they are mutually attractive. Gulick, to be sure, is a racialist, since he believes race exists, and finds no problem in labeling individuals and populations racially according to their putative "race". Nor is he advocating interracial marriage. He is simply not against such marriages if individuals of different races happen to be attracted to each other. What is important is that Gulick advocated raceless citizenship at a time when such an idea was unpopular in the land of the free and the home of the brace. He had been criticized for his advocacy of raceless citizenship, and even snubbed during an appearance before the Senate Committee on Immigration in 1914 -- hence the title of this chapter. Kipling was rightGulick is one of the few writers of his time to understand Kipling. On the second page of Chapter IX he takes to task those who misquote Kipling to defend their racism. The ultimate consequences are pictured in lurid colors. Asiatics, they insist, could not possibly take real part in maintaining a democracy, for they believe in despotism, not only in the government, but also in the family; democratic principles are intrinsically unacceptable tot hem and even unintelligible. Those who present these assertions commonly claim that an unbridgeable chasm separates the Caucasian from the Asiatic mind. They glibly quote the lines from Kipling:

"Oh, East is East and West is West, Pages later, the chapter ends like this (pages 128-129) The alleged unbridgeable chasm between the East and the West is in fact non-existent. The minds and hearts of men are essentially the same, whatever the race. In spite of all their admitted differences, the East and the West have far more in common than appears to the casual traveller and the superficial student. Those who quote Kipling are hardly fair to him when they stop with the lines that correspond to their a prior opinions and fail to quote the lines that controvert them. Immediately following the four lines quoted above, Kipling adds:

"But there is neither East nor West, "Blue-eyed" dollsSidney Lewis Gulick (1860-1945) was born in the Marshall Islands to missionary parents. His father was born in the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) to missionary parents. Sidney's paternal grandparents died in Kobe, Japan, where they had gone live with another of their sons, a younger brother of Sidney's father. Sidney Gulick was himself ordained in the Congregational Church in 1886. For twenty-five years between 1888 and 1913, he served in with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. During his last seven years he was a professor of theology at a university in Kyoto and a lecturer at another. Back in the United States, Gulick campaigned against anti-Asian legislation in California and elsewhere in the country. His efforts failed to halt the Immigration Act of 1924, which all but closed the door to Asian immigration and continued to deny Asian immigrants access to US citizenship. Gulick threw himself into the formation and running of the Committee on World Friendship Among Children. He originated its doll exchange program, under which American children sent dolls to children in Japan. Beginning in 1927, thousands of "Friendship Dolls" were sent to schools in Japan during the Hinamatsuri (doll festival) each spring. Though many of the dolls did not have blue eyes, they came to known in Japan, and are mostly known today, as Aoime no ningyo in Japanese or American Blue-eyed dolls in English. In racialist contexts, "aoime" [blue-eyed] is the Japanese equivalent of "slant" or "sland-eyed" in English. It reflexively substitutes for "foreigner" or "westener" or "American" -- and for other terms that also signify "white" in racialist parlance. During the war, many of the dolls were destroyed because of their association with the American enemy. Today they are proudly displayed in schools that have managed to save them, and there are numerous websites devoted to dolls, which have also come to be prized by collectors. Gulick himself was suspected of being a spy for Japan. According to a grandson, he wrote, regarding his efforts to improve US-Japan relations by revising US immigration laws -- in America, "I am as truly a missionary working for Japan as if I were in Japan." By William Wetherall |

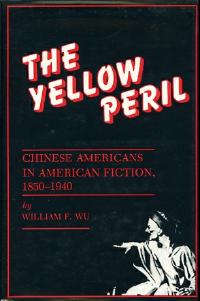

| Yellow peril |

The Asian/Pacific/American Institute was established at New York Univeristy in 1996. Its mission, according to its website at www.apa.nyu.edu, is to (1) "promote discourse on Asian/Pacific America defying traditional boundaries, spanning Asia, to the Americas, through the Atlantic and Pacific Worlds", (2) "dispel socio-cultural and political misconceptions, provide cultural and scholarly connections, lead collections building, and encourage innovative research and interdisciplinary exploration", and (3) "serve as an international nexus of interactive exchange and access for scholars, cultural producers, and communities from New York to beyond." Recent achievements of the institute include the acquisition of the Yoshio Kishi / Irene Yah Ling Sun Collection as part of its effort to "build a foundation of, and preservation and access to, important historical documents and previously overlooked materials for present and future researchers and students." The publication under review commemorates the Archivist of the "Yellow Peril" exibit held at the institute from 3 February to 31 July 2005. The subtitle of the exhibit was "Yoshio Kishi Collecting for a New America". The book, like the exhibit, "provides a historical context/explanation of yellow peril and how this phenomenon came to be." The artifacts in the visual part of the essay are from the collection. The running text was written by Dylan Yeats, who the colophon lists as the editor. The imperative of collectingThe foreword, called "The Imperative of Collecting Xenophobia", was written by John Kuo Wei Tchen, the institute's founding director. Tchen starts with a simple question: Should an XXX-rated inflatable latex "Chinese Sex Girl" be collected or tossed? The book shows only part of the blow-up doll. The on-line exhibition shows all her charms. Tchen, a cultural historians, "can affirm this is an important item to collect" -- but wonders if he would have gone into a sex shop and bought one himsel. Someone has to wonder what such sex toys mean -- "How do the allures and fears of sexuality and race interlink?" "Each item has its shadow," Tchen says, and "We need to archieve the shadows." One problem everyone faces is what to keep and what to toss. Every person who gathers anything for whatever reason, or who inherits anything, has to do a triage. Somethings are saved. Other things are thrown, dumped, burned, or buried. As Tchen writes, though, there are both personal and social considerations (page 1).

Tchen concludes his generally interesting and colorful foreword on this note (page 3).

"Japanese in the U.S."In his foreword, Tchen pursues the "imperative of collecting" theme in terms of the "categories" that librarians and other archivists have placed materials -- "Yellow Peril" -- "Orient". Such terms began to vanish from libraries in the 1970s (page 3).

Tchen does not say why, for example, "Japanese American" is better than "Japanese in the U.S.". He probably assumes that most of his readers will understand that -- in the minds of not a few people -- "Japanese in the U.S." continues to embrace Americans who happen to be of Japanese ancestry, but who are not Japanese. Tchen does not appear to understand that such racialism -- such conflation of nationality with putative race -- is a problem everywhere. In Japan, too, most people will speak of "Japanese Americans" as though they are "Japanese in the U.S.". The problem with Tchen's own reductionism -- his conflation of "Japanese in the U.S." into "Japanese Americans" -- is that "Japanese in the U.S." is in fact a very appropriate term if it means precisely "Japanese in the U.S." -- namely, people who, regardless of their race or ethnicity, are nationals of Japan who happen, for whatever reason, to be in the United States. For this would be the legal sense of the term -- reflecting usage in both US and Japanese government statistics which report the number of Japanese nationals who in the United States. One is not entirely sure -- from Tchen's usage of "Japanese Americans" -- what he means by "Japanese" and "Americans". Presumably "Americans" is a nationality. Presumably "Japanese" is a national ancestry. If so, then "Japanese American" would have to include all people who are Americans by nationality and who, in their personal histories, have some family or other connection with Japan or Japanese nationality -- regardless of their racial ancestry -- since, under Japanese law, Japanese nationality is a raceless civil status. One gets the impression, though, that Tchen is merely swapping one racialist label for another. His inclusion of "Japanaese in the U.S." with "Japanese Americans" also contributes to the dumbing down of history that is rampant everywhere. The following remark later in the work is a case in point (page 27, underscoring mine).

The rhetoric -- "imprisoned" and "concentration camps" -- though not without foundation -- is not entirely accurate. Historical understanding is not achieved merely by replacing government and other euphemisms with what I would call "critically correct" terminology. The main problem in the above citation, though, is the characterization of the "prisoners" as "120 American citizens . . . along with all persons of Japanese ancestry" living on the West Coast in early 1942. It is simply not true. In the April 1940 census, there were roughly 127,000 people in the United States of Japanese ancestry. Of these, about 47,000 had been born in Japan, and practically all of the Japan-born were Japanese nationals. Of the roughly 112,000 people of Japanese ancestry who were living on the West Coast, about 70,000 were Americans and the rest were Japanese. Elsewhere in the United States -- unrelated to West Coast exclusions -- Japanese officials and other a number of other Japanese were taken into custody as enemy aliens. In some cases, Americans (including Americans of Japanese ancestry) accompanied their enemy alien spouse or parents into detention. Most of these detainees were repatriated to Japan within a year or two of their detention through civilian exchange agreements between the United States and Japan. Various local Civilian Exclusion Orders provided that "all persons of Japanese ancestry, both alien and non-alien" be "evacuated" from the West Coast military zone. In this implicity racial definition of "Japanese", the term "aliens" -- because there were no grounds to include "non-aliens" except as a racist metalegal afterthought. The "exclusions" and "evacuations" were based on Executive Order No. 9066 of 19 February 1942, which stated only "enemy aliens". The order cited, as its authority, the same 1918, 1940, and 1941 acts cited in Executive Order No. 8972 of 12 December 1941. These acts, and their post-9/11 21st-century cousins, stem from enemy alien and sedition laws going back to 1798. The number of people who were excluded from the West Coast, by internment in one of the several "relocation centers" or camps established for "persons of Japanese ancestry", is commonly pegged at 120,000. Apart from the accuracy of this figure, about one-third of the internees were in fact "Japanese in the U.S." -- and only about two-thirds were "Americans" defined as "American citizens". The Japanese internees included mostly settled immigrants. Very few of this "first generation" chose to be "repatriated". Some of the "second generation" were dual nationals, and some of these dual nationals had been partly educated in Japan. But very few of these Americans chose to renounce their US citizenship and leave the United States.

|

Dan Gilbert This wartime publication (March 1943) has six short chapters. 1. Why Japan Will Outlast Germany 2. What Japan Will Do After Germany Is Beaten 3. Will Japan Make an Ally of Russia? 4. Japan's Plan to Seize the Holy Land 5. Is Japan the Antichrist Nation? 6. Can China Survive? The penultimate chapter is obviously where this Man of God is coming from. It draws largely from Syngman Rhee's Japan Inside Out, published in 1941 by Fleming H. Revell, whose mission it was to spread Christianity. Gilbert concludes that Japan's mission was otherwise (page 42). Japan is waging, primarily, not a war of conquest but a religious war. Her aim is to destroy Christianity -- first in China, and then throughout the entire world. To accomplish this objective she must unify the yellow peoples of Asia, not only by means of her military program, but under the inspiration of her religious superstition. Zondervan Publishing House, now a division of HarperCollins, is still in Grand Rapids, Michigan. It still specializes in Bibles and evangelical Christian tracts, and claims to be "the leading Christian communications company in the world". Today, though, its publications are mostly concerned with teen sex and whether the United States can be a Christian nation. (WW) |

Bill Hornadge The first paragraph of the preface: Australians, particularly when travelling abroad, try desperatelyi to cultivate the idea that they are a tolerant, racially unprejudiced people. They have worked so hard at buildling up this image that most of them now believe it to be true, but in reality the average Australian is as xenophobic and racially prejudiced as the next man. That this is not immediately apparent to the brief visitor to these shores is only because colour problems do not exist in Australia on the massive scale they assume in some other parts of the world. Wherever colour does intrude on the consciousness of the average Australian, the reaction is immediate -- and ugly. And the last paragraph: Racism in all forms will be eradicated only if it is dragged from its cesspit into the open and its exponents forced over and over again to justify in the cold light of day their prejudices and fears. The cold blasts of sunlight, and the logic of commonsense may eventually drive the evil from the planet earth, but that day is a long time in the future. |

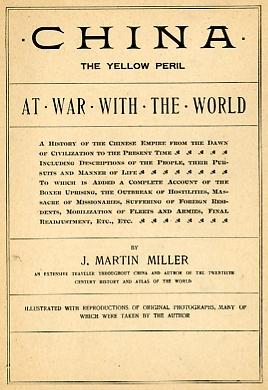

J. Martin Miller This book is one of the most interesting publications to appear in 1900, immediately after the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion, which some Euroamericans saw as evidence of what Kaiser Wilhelm II, following the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895, had called "gelbe Gefahr" or "Yellow Peril". European and Japanese perilsThe book is particularly interesting because, though "The Yellow Peril" appears on the title page of the edition under review -- and though one chapter describes the "Two Months of Peril" faced by the foreign legations that were besieged by Boxers in 1900 -- its author did not, in fact, endorse a "yellow peril" thesis but, quite the opposite, he publicized the view of a prominent Chinese statesmen who advocated that China needed to defend itself against what amounted to a European peril and a Japanese peril. The spine of the edition under review reads "China / Past and Present / Illustrated". The front cover reads "China / Past and Present / Her History, Geography, Literature, Art & Religion. / Her People, Products, Customs, Commerce & Boxer-Uprising." Another edition bears the title "China / Ancient and Modern" on a decorative tan cover. Yet another edition is supposed to have a navy blue cover. Other editions are said to have been published by Occidental Publishing Company (San Francisco), Sanderson-Whitten Publishing Co. (Los Angeles), Earle Company Ltd. (St. John), and Haskell (Norwich). ContentsMiller introduces China historically and describes Chinese society as he observed it at the end of the 19th century. But the last 9 of his 28 chapters deal entirely with the Boxer disturbances that unfolded after the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895, broke out in open violence in 1898, came to a head with the intervention of foreign military forces while Miller was in China, and was settled by the Boxer Protocol of 1901, a year after Miller's book was published. 1. The Country of the Chinese 2. In the Dawn of History 3. The Growth of a Great Empire 4. Early Contact with European Powers 5. The Opium War with England 6. Foreign War and Internal Rebellion 7. Great Cities of the Empire 8. The Government of China 9. Domestic Life and the Family 10. Customs and Costumes of the Chinese 11. Holidays, Sports and Games 12. The Chinese Language and Literature 13. Religions of the Chinese Empire 14. Art, Music and the Drama 15. China in Science, Invention and Discovery 16. Resources and Industrial Wealth 17. War with Japan in Korea 18. Foreign Relations Since the China-Japanese War 19. Great Men in Modern China 20. Beginning of the "Boxer" Outbreak 21. From Taku to Tientsin 22. "On to Peking" 23. The Siege and Sack of Peking 24. Two Months of Peril 25. Stories of Personal Experience 26. Chronicles of Horror 27. In the Imperial City of Peking 28. Formulating Terms of Peace Boxer RebellionWhat Miller called the Boxer "uprising" or "outbreak" is now most often dubbed a "rebellion". An incredible amount of ink has been spilled in Chinese, Japanese, English, and other languages over the events surrounding August 1900, when foreign troops invaded, occupied, and looted Beijing -- an incident which nationalists and communists alike look back on as the most humiliating in China's recent history. The Boxers disliked the unequal treaties the Qing court had been forced to sign with foreign powers over the years, including most recently Japan after the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895. The Shimonoseki Treaty of 17 April 1895 ceded Japan not only Taiwan but the Liaodong peninsula. But on 23 April France, Germany, and Russia -- in what is called the Triple Intervention -- forced Japan to cede Liaodong back to China. The killing of two missionaries in Shandong province in 1897 gave Germany the excuse to occupy the port of Qingdao in eastern Shandong (Shantung) in November. The next month Russia occupied Lushunkou (Port Arthur) on the Liaodong (Liao-tung) peninsula in Liaoning province in northeast China and forced China to lease it the peninsula. Britain then snatched the seaport of Weihai (Weihai Garrison) to the east of Qingdao (Tsingtao), and in 1898 France occupied the fishing port of Zhanjiang (Fort Bayard) in Guangdong province in southeast China. The Boxers -- as the "Yihetuan" or "Righteous and Harmonious Fists" were dubbed in English -- were inspired by beliefs in their religious invincibility, and by nativist resentment of foreign influence in China, to purge the country of foreigners, above all missionaries. The group originally directed its discontent against the Qing court, of Manchu origin. But it was then coopted by the Empress Dowager Cixi, who also wanted to rid China of its foreign occupiers. In June 1900, the Boxers, with imperial troops, attacked foreign compounds in Tianjin (Tientsin) and Beijing (Peking). The missions of Belgium, France, Japan, the Netherlands, Russia, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States were close enough together in Beijing that they were able to link their defenses and provide a refuge for foreigners in the city. But the German legation, in another part of the city, was over run, and the German envoy was taken captive and killed. The diplomatic response was to form the Eight-Nation Alliance, consisting of Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. A number of navel and other military actions took place in June and July, but things came to head, and the Boxers were finally defeated, in August. The alliance was able to pool about 50 warships, 5,000 marines, and 50,000 soldiers. Japan contributed 18 warships and over 20,000 troops, nearly twice as many as either Russia or Great Britain. Some anti-Boxer Chinese soldiers also joined the action. LootingTianjin was captured on 14 July, and it was from there that the alliance mounted its 4 August attack on Beijing. This is the subject "On the Peking" (Chapter 22) in Miller's book. As Miller describes the action, the Japanese troops are well organized, out in front, not afraid to take the initiative, and admired for their bravery in battle. When it came to "The Siege and Sack of Peking" (Chapter 23), though, two interesting things develop. One is that Japan attempted to gain control of the Imperial Palace and protect it against destruction before contingents of other nations could attack and presumably destroy it. Miller cites an unnamed "writer from the scene of conflict" (page 386). [At the gates of the walled Imperial Palace in the heart of Beijing] "The Japanese had plans of their own, which had not been reckoned with [by others parties in the alliance]. They were trying to protect the Purple city and establish communication with some one there who might be made to represent the Chinese government, so as to open the way for beginning negotiations for the settlement. Now they were sending a battalion of infantry to each of the main gates of the Imperial city to guard them and, if possible, prevent any violation of the palace." However, the regiments of the other nations began mounting attacks against one gate or another. Eventually it became a free for all, and the looting began anew (page 392-393, bold emphasis added). "Now the foreigner has laid his heavy hand on the wreck, and the condition is steadily growing much worse. The looking is going on more easily and evenly than it did in Tientsin. Here there are not so many Chinese lying around watching for their chance. They are fewer and vastly more timid. In their own quarter the Americans are supposed to stop looting entirely and the report is that there are orders to shoot. The British are going at the thing quietly and systematically, sending out their pack trains with a party in charge of each under command of an officer. All the loot goes into the big pile in the legation compound and will be put up at auction. Then, when it is all sold, Tommy will get his share of the prize money. It is a very comfortable and easy way and not liable to heart burnings like ours. [Note: Apparently Miller's source is an American.] "The Russians and French loot joyously and spontaneously, without effort. They gather up what they like, and as far as they can they take it from the quarter of the city in which they happen to be. . . . Here more kinds of look came out than in Tientsin. The furs were much better. So with some of the silk, but there are bits of green stuff they call jade, and one hears of old plates and priceless vases and that sort of thing. And for sycee [coins], if the soldiers had a way to dispose of it, probably every one of them would be paid to his satisfaction for coming to Peking. Only the Japanese stand aloof, see it all, but take no part in it, and say it is all wrong. Chinese atrocities"Two Months of Peril" (Chapter 24) is Miller's reconstruction of the suffering endured by those who defended the foreign legations in Beijing until they were rescued in August. He gives an account of how the chancellor of the Japanese legation, "while riding a jinricksha outside the Yung Tung gate of the southern city, was assaulted and killed and his body was never recovered. An imperial [Chinese] edict denounced the murderers, but its authors failed to perceive that this act was part of the harvest reaped from the dragon's teeth sown so freely by the Empress Dowager and her advisers" (page 407). In "Stories of Personal Experience" (Chapter 25), and especially in "Chronicles of Horror" (Chapter 26), Miller relates reports of butchery committed by Boxers, in order to convince the reader that foreigners and Chinese in the besieged legations had good reason to fear that they would be massacred should they be overrun. He does not himself provide numbers of casualties, but other sources suggest that, by the time the fighting ended on 14 August 1900, the Boxers had killed roughly 20,000 people, including about 230 missionaries and hundreds of Chinese Christians, and thousands of insurgents, supporters, and bystanders. Allied atrocitiesMiller's "Chronicles of Horror" runs 23 pages. The last 8 or 9 are devoted to stories of allied army atrocities, and begins like this (page 448). Not all of the atrocities, however, were committed by the Chinese. The spirit of revenge seized upon the soldiers of the allied armies, and the Russians, French and Germans particularly displayed a cruelty even less excusable than that of the Chines, if the obligations of enlightenment be considered. Citing accounts by people who were there, Miller reports atrocities committed by Russian police and Cossacks against Chinese civilians in settlements along China's northeast border with Russia, and atrocities committed by French soldiers in the course of looting the city of Tongzhou (Tungchau) a few miles east of Beijing. Regarding the latter, Miller cites the account of an American physician who had practiced in Beijing for many years and remarked that he "was one of the besieged in Peking and for sixty days expected nothing but death and torture at the hands of the Chinese" (page 452). "The native reports of the disgraceful behavior of the allied armies' troopers stationed in Tungchau having reached headquarters in Peking, General Chaffee, fearful lest his own soldiers should be implicated, decided to have the matter fully investigated. He therefore dispatched Major Meur and an interpreter to Tungchau to inquire into the occurrences. Before leaving Peking the belief as that Russians and Japanese were the principal offenders, but the investigation proved the Japanese to be entirely innocent, the Russians scarcely implicated at all, but the French to be the worst offenders." "It is from the German correspondents and the German press that confirmation of the charge of German brutality is received," Miller writes. "The cruelties reported are becoming alarmingly numerous. An appalling story is told in two letters sent from Peking by members of the expeditionary corps" (page 455). Miller cites only the first letter, and lets its gruesome account, and condemnation, stand without comment. "China's only hope"Miller ends the book on an interesting note. He expresses faith that "the Chinese mind" is perfectly capable of "grasping the western man's point of view" and cites. He cites at length words from a treatise written in Chinese by statesman and educational reformer Chang Chih-tung (Zhang Zhidong, 1837-1909) soon after China's war with Japan in 1894-1895. Fleming H. Revell published Chang's treatise as China's Only Hope: An Appeal (translated by Samuel I. Woodbridge, introduced by Griffith John) as Miller was writing his book. Miller assures his reader that "Who, after reading them [passages from Chang's book], can deny that the Chinaman, whatever his mental plane and point of view, may be thoroughly well aware of the meaning of the game of diplomacy as played by the more civilized powers?" (Page 489-490). Miller has already quoted Chang to have said that Japan became prominent because of men who "visited foreign countries twenty years ago and learned a method by which to escape the coercion of Europe." China, Miller says, paraphrasing Chang, "must send men to Japan, and later probably to Europe" to gain the knowledge it needs to survive. Miller goes on to cite more paragraphs from Chang's book, and the last one he cites reads like this (page 490). "With fifty warships on the sea and thirty myriads of troops on land . . . what country would dare begin hostilities against China, or in any way infringe upon her treaty rights? We would be in a position to redress our wrongs without the fear of staking all upon minor issues. Under these conditions Japan will side with China, Europe will retire and the far east will be at rest." Miller adds only one comment to end the book (page 490). Whatever other conclusions may be drawn, the viceroy's interesting volume affords a remarkable proof of the fact that the Chinese, when he does awaken, may be found with an unexpectedly clear perception of the problems which confront him. "The Yellow Peril"Having crafted what is essentially a fairly objective account of China at the time of the Boxer Rebellion -- and having made it so clear that China was a victim of its own political ineptness and then prominently publicized Chang's hope for a strong, independent China that need no longer fear either Japan or Europe -- why "The Yellow Peril" on the title page? "At War with the World" alone would have said all that needed be said about China's political predicament at the start of the 19th century. What is particularly fascinating about Chang's (more than Miller's) view of what China needed to do to stand on its own feet is that (1) China's inability to heed his advice left China open for further lose of its sovereignty to foreign powers, particularly Japan -- though Japan claimed it was only defending China against Russian and other foreign incursions, and (2) China is defending its sovereignty today as Chang advocated it should a century ago. (WW) Who was J. Martin Miller?China is sprinkled with 47 full-page reproductions of photographs, many of which were "gathered" by the author during "a prolonged journey through the Chinese Empire in 1899". Miller is credited with another photograph from the times, showing "Seven white men in Manchu dress, with queues, stand talking together" in the words of Rolland Marchand, who teaches history at the University of California at Davis. |

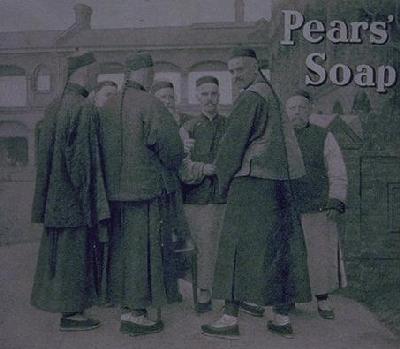

Soap and Christianity The image to the right is copped and cropped from The Roland Marchand Collection on the History Project website of the University of California at Davis. The text below the image is shown here more or less as it appears in the scan of the entire ad from which the image was cropped. The ad ran on page 5 of the advertising section of St. Nicholas Magazine. It speaks for itself . . . to a point. The ad does not say whether J. Martin Miller wrote the letter knowing it would be copy for an ad -- or whether he wrote it with a wink inspired by a journalist's cynical sense humor. |

||||||||||||||||

Prolific correspondentEither way, James Martin Miller (1859-1939) was a prolific writer, and apparently also a publisher of maps. Bret Wallach, a professor of geography at The University of Oklahoma, refers to him as "a well-known war correspondent of the time" in an article about Oklahoma in the late 19th century. Miller, who was raised in Winfield, Kansas, close to the border of what is now Oklahoma, recollected "the coming of troops to the Kansas line with men [outlaws] chained behind wagons." Kansas had become a state in 1861. Oklahoma Territory was formed out of Unassigned Lands and No Man's Land in 1890, and the Territory became a state in 1907. In addition to China, which appears to be his best known book, Miller wrote, edited, or coedited the following volumes, among others. (WW)

|

The Writings of Dr. Revilo P. Oliver Revilo Pendleton Oliver (1908-1994) spent much of his life championing antisemitism and a long list of other causes that liberals love to hate him for. His fans call him "Dr." because he had a Ph.D. -- which in his case must have meant the "piled higher and deeper" degree that follows a BS (bull shit) and MS (more of the same). Oliver a professor of Classics at the University of Illinois for over thirty years. Why a scholar of classical philology, Spanish, and Italian should become a founding member of the John Birch Society in 1958 is not surprising in the light of his white supremacist, antisemitic beliefs, and his communist, homosexual, and liberal phobias. JBS must at least be credited with expelling him in 1966 because of his public racism. ContentsThis collection of articles was apparently published by a fan wants to keep Oliver's thoughts in circulation. It consists of five single-spaced articles printed on one side only of fifty-one unnumbered spiral-bound pages. The Yellow Peril, 1983, 30 pages What We Owe Our Parasites, 9 June 1968, 13 pages A Bible Student, December 1984, 1 page The Bible Came From Arabia!, December 1984, 3 pages The "Holohoax", November 1984, 4 pages Oliver wrote "The Yellow Peril" at a time when Japan was at the height of its postwar industrial growth and seemed about to buy everything of value in North America and Europe. It is the age of "Japan bashing" on the part of Americans, in particular, who believe that Japan is playing, unfairly, by its own rules. Oliver cites a Business Week article at the time which quoted a Japanese official as saying "The Japanese can manufacture a product of uniformity and superior quality because the Japanese are a race of comparatively pure blood, not a mongrelized race as in the United States" (the italics are Oliver's). This "simple and obvious fact naturally provoked hysteria" according to Oliver. He is not sure where the "screeching about 'bigotry' and 'racism'" came from -- "whether this standardized slop came from Jews or high-minded nitwits; it probably came from both." Oliver is dead certain, though, that behind the rise of Japanese might are Jews in the guise of Japanese. He was convinced, as were those he cites, that the Jews had reached ever part of the world, and proceeded to "bamboozle and exploit the natives", long before the so-called "diaspora" -- which, like the Holocaust, he considered a hoax. If Japan is deeply infested with Jews, she is doomed, and the details of her ruin would be of no interest, even if we could foresee them," Oliver writes. "If she is not, she has a formidable potential, and unless she is destroyed by some external force, she will determine some part of the future of life on this globe. . . . Some of our descendants will probably survive to become the Ainu of Europe and North America." Unfunny comic reliefWe are not yet half way through Oliver's essay, and he has just been warming up. Seventeen pages later, after taking us on a tour of Japanese history and literature -- during which he invokes everyone and everything from Lafcadio Hearn, Genji, the Mishima, Zen, bushido, Romans, the Sassoons, the Jewess Soong Ching-ling, Mao and the Yellow Jews of China, Rabbi Kissinger, Anne Frank's Diary, and Mark Twain -- he concludes with these words. If this analysis of the Jews' racial instinct is correct, it answers our initial question. It is most unlikely that the Jews will wish to abate the growing industrial supremacy of Japan so long as its effect is to weaken us, induce economic prostration, and accelerate our race's already vertiginous progress to extinction. The greatest reason I can think of reading Oliver's mad jottings is that they offer page after bristling page of comic relief from the propaganda on the far left of the spectrum. The fact that some people are ignorant and paranoid enough to believe the rantings of either extreme is not, however, funny. (WW) |

Paul Wong, et al (editors, curators) The images in this publication represent the photographs, films, and videos that were presented in the Yellow Peril: Reconsidered exhibition that toured Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, Halifax, Vancouver, and Ottawa in 1990 and 1991. Examples of the work of each contributing artist are grouped by type of media, following six essays which are listed on a contents page headed "Le Peril jaune". Yellow Peril: Reconsidered (Paul Wong) Belong in Exclusion (Monika Kin Gagnon) Multiculturalism Reconsidered (Richard Fung) Neither Guests Nor Strangers (Larissa Lai and Jean Lum) Broadcast Blues (Anthony Chan) A Displaced View (Midi Onodera) The forefront of artThe Preface explains that Yellow Peril: Reconsidered is the third in a series of exhibitions that "focus on the works of Asians in the New World" (page 4). The first, called Asian New World, was held in Vancouver, and presented video works by Canadians and Americans. The second, called Yellow Peril: New World Asians, was held in London, where it "received curious, and mixed, reactions" (ibid.). The UK has a well developed "Black Arts" (artists of colour) movement. Much of that work refers to issues of decolonization and the effects of living in what was once the colonial power base of the English empire. Within that context, Yellow Peril: New World Asians was seen as peculiar, a prominent exhibition from the colonies featuring the work of Asians. The photoworks and videotapes were exported from the colonies and presented as an import in what had been the centre of imperial power. The exhibition and participants were not viewed as marginalized. They were seen as serious artists presenting important new work at the forefront of Canadian Art. As the cover of this book suggests, the graphic images presented in Yellow Peril: Reconsidered were undoubtedly then, and are probably still, at the forefront of art, Canadian or other. (WW) |